It's a Random, Uncertain, Unpredictable Life

What "It's a Wonderful Life" tells us about the nature of reality

The Frank Capra classic It’s a Wonderful Life is one of the most beloved films ever made. It’s a Christmas classic. Countless people who seldom watch movies repeatedly happily sit down each year to watch George fall for Mary, struggle to build homes for the town, fall into despair, then be lifted back up by an angel and the good people of Bedford Falls. I’m one of them.

But there’s something about It’s a Wonderful Life you may not know: It illustrates fundamental facts of reality that we routinely overlook and, in doing so, fool ourselves into thinking we know far more than we really do. Or to put that in polysyllabic terms, It’s a Wonderful Life can help us better understand epistemology and be a lot more humble. Which is impressive for a sappy movie about an angel saving a man.

This insight isn’t found within the film itself, however, but in the history of a movie: It was shot in 1946 and was widely released in 1947. But it also had an early release in December, 1946, so it would be eligible for that year’s Oscars. The film was directed by the hugely popular Frank Capra. It starred Jimmy Stewart, who had been one of the biggest names in Hollywood before the war and returned a highly decorated hero. If ever a movie was a sure thing for Oscars, this was it.

(Jimmy Stewart was the first Hollywood star to volunteer, incidentally. And he refused to do the cushy, safe work most celebrities were given. Instead, he became a bomber pilot in Europe. In four years, he was promoted from private to colonel and was awarded both the Distinguished Flying Cross and the French Croix de Guerre.)

But when It’s a Wonderful Life opened, reviews were mixed. The New York Times exemplified the reaction. The picture has some good qualities, the reviewer said. Jimmy Stewart is super. But on balance?

The late and beloved Dexter Fellows, who was a circus press agent for many years, had an interesting theory on the theatre which suited his stimulating trade. He held that the final curtain of every drama, no matter what, should benignly fall upon the whole cast sitting down to a turkey dinner and feeling fine. Mr. Fellows should be among us to see Frank Capra’s “It’s a Wonderful Life,” which opened on Saturday at the Globe Theatre. He would find it very much to his taste.

…

Indeed, the weakness of this picture, from this reviewer’s point of view, is the sentimentality of it — its illusory concept of life. Mr. Capra’s nice people are charming, his small town is a quite beguiling place and his pattern for solving problems is most optimistic and facile. But somehow they all resemble theatrical attitudes rather than average realities. And Mr. Capra’s “turkey dinners” philosophy, while emotionally gratifying, doesn’t fill the hungry paunch.

Still, the studio believed the picture could win at the Oscars. It launched a major promotional campaign that paid off with six nominations, including Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Actor.

It’s a Wonderful Life won only one Oscar. Not for Best Picture. Or Best Director. Or Best Actor. It won a technical achievement award for its depiction of falling snow.

Worse, It’s a Wonderful Life disappointed at the box office. It wasn’t exactly a flop, but it had been expensive to make, so its middling financial return meant it lost a fortune. You know that wonderful image of a clanging Liberty Bell at the start of the movie? “Liberty Films” was a production company founded by Capra and a partner. It only ever made two films because the losses on It’s a Wonderful Life were so severe it sank the company. Capra thought his career was effectively over.

And that was that. It’s a Wonderful Life wasn’t a bad movie. It was good, in fact. But there are lots of good movies. And as is the fate of most good movies, It’s a Wonderful Life was soon forgotten.

Until some person unknown to history made a clerical error.

The Copyright Act of the time stipulated that creative works were protected for 28 years but the copyright could then be renewed. The rights to the movie had been sold and resold, so the company that held the rights after 28 years had to file paperwork to extend them. It didn’t. It’s A Wonderful Life became public property. Anyone could show it, at little cost. (The full story is more complicated than this, as full stories usually are. But for our purposes, further details don’t matter.)

Television stations have a lot of airtime to fill and the list of Hollywood movies whose copyright accidentally expired is not long. So in the early 1970s, It’s A Wonderful Life went into high rotation on American television sets. And its fate was transformed.

Only after this was It’s a Wonderful Life seen as a Christmas movie. Only after was it embraced as a beloved classic. Only after did it become a common entry on lists of the all-time great movies and only after was it declared “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant” by the US Library of Congress and added to the National Film Registry.

Happily, Frank Capra lived long enough to see his movie’s rebirth. He was thrilled. And dumbfounded. “It’s the damnedest thing,” he said.

Now, you may be thinking, “that’s a lovely story but where are the profound insights into the nature of reality?”

To see them, think about the simple, clear, concrete explanations we usually have for why something turned out the way it did. The human brain is superb at generating these under any circumstances, but with works of art the explanations come particularly quick and easy.

Why is the Mona Lisa the world’s most famous painting? Because it’s the world’s greatest painting.

Why is Shakespeare the world’s most famous playwright? Because he wrote the world’s greatest plays.

In these explanations, outcomes are the result of a work’s inherent qualities. Great works are recognized. Duds fail because they’re bad.

Sometimes, we add a second, external factor, and say the success was the result of the work’s quality plus that external factor. Most cultural commentary consists of stories like these.

Why was the low-budget zombie movies 28 Days Later such a sensation in 2002? Because it was an excellent movie skilfully directed by Danny Boyle, the critic would say, and it reflected the crippling anxiety of living in a time obsessed with the threat of terrorism.

Why was Bridgerton such a hit on Netflix in 2020 and 2021? Because it was the escapist fantasy people wanted when they were sitting at home and feeling beaten down by the pandemic.

Why was Squid Game a sensation on Netflix in 2021? Because it perfectly reflected the claustrophobia and hopelessness of being shut up at home, feeling beaten down by the pandemic.

But notice that the explanations for the successes of Bridgerton and Squid Game directly contradict each other. And notice I haven’t provided any actual evidence for any these claims. These are, at best, plausible hypotheses. But unlike how scientists handle hypotheses, we almost never subject these claims to serious critical thought. Or demand real evidence beyond their mere plausibility.

Again, let me emphasize that this is not limited to artworks and culture. The human brain generates explanatory stories as easily as it regulates breathing. We observe circumstances as we know them at the moment, we generate a plausible explanation, we feel we know the truth. Rinse and repeat a hundred times a day. That’s what the brain does.

So why is It’s a Wonderful Life a beloved classic? Instinctively, we point to the movie’s qualities. It’s beloved because it’s excellent.

Or that’s what we would do if we didn’t know the movie’s history.

Once we do know the history, it becomes harder to make that simple, commonplace explanation. After all, it was the same movie in 1947 when critics were indifferent to it. When it lost a truckload of money and sank the production company. When the only Oscar it won was for the superb quality of the snowflakes.

Once we know the history, we know that it only came to its current prominence after it went into high rotation on American TV in the 1970s. And that only happened because of an accident.

Once we know the history, it’s impossible to deny that It’s a Wonderful Life could easily have disappeared and been completely forgotten. It becomes clear that what actually happened is only one possible outcome, there are others, and those others may even have been much more likely. And what made the difference between one outcome and another were things done and not done which, at the time, to those involved, would have appeared to be trivial.

And I’ve only scratched the surface of the factors that determined the outcome. Dig deeper and you have no choice but to conclude that the particular chain of events that occurred — culminating in It’s a Wonderful Life becoming a beloved classic — was wildly improbable.

Twists of fate determined by seeming trivia like this may seem rare. They’re not. What is rare is knowing how a particular twist of fate came about. We can even say that the wild improbability of Its a Wonderful Life becoming a beloved classic is actually commonplace. We are surrounded by wild improbabilities all the time, as I’ve written before.

Doubt all this? Read a good history of Shakespeare and his works and in no time you will discover countless ways in which the they may never have been put on the highest pedestal. Or even come into existence.

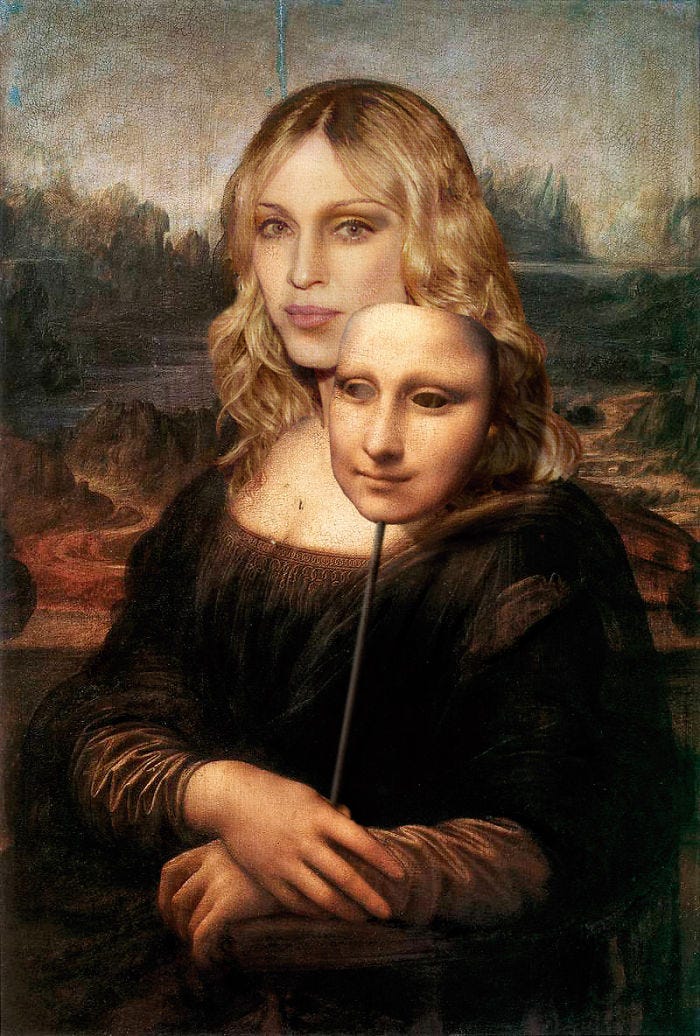

Or consider the history of the Mona Lisa. It was always considered an excellent painting. But there are lots of excellent paintings and that’s how people felt about the Mona Lisa. It was never considered the apex of art. For centuries, critics didn’t even include Leonardo da Vinci to be on the top tier of painters, with Titian and company.

So how did the Mona Lisa, painted in 1503, get to be the most famous painting in the world? More importantly, when did that happen?

We can date it precisely. It started in 1911.

That year, the Mona Lisa was stolen by a Louvre employee named Peruggia. He had it for two years and was arrested when he tried to sell it. The case was a sensation in France — and in Italy, where Peruggia was treated as something of a national hero because he was Italian and tried to sell the Italian master’s painting to an Italian museum. “From that point on, the Mona Lisa never looked back,” wrote Duncan Watts in Everything is Obvious. “It became a reference point for other artists — most famously in 1919, when the Dadaist Marcel Duchamp parodied the painting by adorning a commercial reproduction with a moustache, a goatee, and an obscene inscription.” Countless others did something similar. The Mona Lisa became woven into high art and popular culture in a way it never had been before. And that is when it became the world’s most famous painting.

“It is impossible now to imagine the history of Western art without the Mona Lisa, and in that sense it truly is the greatest of paintings,” Watts writes. “But it is also impossible to attribute its unique status to anything about the painting itself.” But still, lots of art critics continue to to exactly that.

The fundamental nature of reality exposed by the history of the Mona Lisa and It’s a Wonderful Life is that outcomes are massively dependent on complex webs of circumstances. A tweak to the web here, a fiddle there, and you may get a dramatically different result.

Still, you may scoff. And not unreasonably.

The current status of the Mona Lisa and It’s a Wonderful Life may have depended on a strange series of circumstances. But how can I generalize? People often treat stories like these as freakish exceptions. Maybe they are right to do so.

There’s something to that objection. The only way to really settle things would be to take a big smash — Star Wars, say, or the Dan Brown novel The Da Vinci Code — and rerun reality a hundred times. See if you get the same outcome every time. Or if you want to do lab-quality work, rerun reality a hundred times with the same conditions at the outset, but then run it a hundred times with a tiny tweak (release it a month later) and run it a hundred times with a different tweak (a different actor plays Luke) and a dozen others. Do you still get the same outcome every time?

Sadly, we lack the godlike power to reset reality. But Duncan Watts and two colleagues — Matthew Salganik and Peter Sheridan Dodds — conducted a landmark study which comes as close as humanly possible to replicating that experiment.

In the early years of this century — before music streaming services were cheap and ubiquitous — the researchers created a website where people could listen to songs and download what they like for free. Critically, visitors were randomly assigned to one of eight experimental conditions. In one, they would simply be shown a list of songs they could sample and download independently. In others, they got the same information but they could also see how many times a song had already been downloaded, which is a strong signal of its popularity. In effect, these were eight parallel worlds.

If the qualities of a song were all that determined how popular a song was, the outcomes would be the same in each world. If the qualities of the song were irrelevant, the outcomes should be completely different in each world.

What they found was something of a mix. The qualities of a song mattered. Some songs tended to consistently do better in all worlds while others songs were consistently lower down. But extreme hits and flops? There was no consistency. A smash in one world was a middling success in another; the worst stinker in one world was merely mediocre in another.

As the authors summed up: “The best songs rarely did poorly, and the worst rarely did well, but any other result was possible.”

Remember, these are very simple worlds without the blizzard of tiny complications we deal with in the real world — things like copyright laws and clerical errors. But even in these simple worlds, a tiny bit of randomness like one or two people deciding early on, for whatever reason, to download this song and not that song could prompt others to do the same, and so on, until it snowballed. One song becomes a blockbuster, while the other is middle-of-the-pack — but only in one world. In another world, the mediocre song becomes the blockbuster and the blockbuster becomes mediocre.

Why are book publishers and music companies and movie studios so bad at predicting which works will be hits? Because the predictability of what they are dealing with is strictly limited. And the one thing they most want to know — which will be the giant smash? — is impossible to predict.

Release It’s a Wonderful Life in one world, and it’s an all-time classic. Release it in another and it’s soon forgotten.

Now, let’s toss in what Robert Merton called the “Matthew Effect.”

Picture a largely unknown author named Dan Brown. He publishes The Da Vinci Code, gets extremely lucky, and The Da Vinci Code becomes a massive, global bestseller.

Dan Brown writes another book, the publisher gives him a gigantic advance, and then…? The publisher spends a fortune promoting the new book. Book stores give the new book the most prominent placement. The media run lots of stories about the new book. Because it’s Dan Brown. Everyone knows Dan Brown. Everyone knows that everyone reads Dan Brown. Everyone expects this new book to be a big hit — and that expectation leads people to act in ways that increase the probability of exactly that happening.

If the new book is indeed another hit, the cycle continues. Dan Brown goes from success to success. Why does Dan Brown sell truckloads of books? Pop culture critics will gin up explanations. But the real reason Dan Brown sells truckloads of books is that Dan Brown sells truckloads of books.

The “Matthew Effect” can be summed up as: Advantage creates advantage; deficit creates deficit. Merton took the name from a passage in the Book of Matthew: “For to every one who has will more be given, and he will have abundance; but from him who has not, even what he has will be taken away.” The rich get richer and the poor, poorer.

Most people find all of this deeply unsatisfying. Even unsettling. It suggests that randomness is vastly more important in the world than we realize. That reality is much less predictable. That we know much less than we think. That we have far less control than we imagine. And it utterly confounds the desire we often feel to believe that the world is, in some fundamental sense, just — that Dan Brown is one of the most successful authors in history because he is wonderful writer who deserves that success.

If you feel that way, I am sorry for harshing your buzz. But reality is what reality is.

Ironically, It’s a Wonderful Life itself strongly hints at this reality.

George Bailey sacrifices his dreams for his family and his town but is tormented when everything he worked for seems set to collapse. He wants to kill himself. But Clarence the angel, with an assist from God, resets the world to show George he doesn’t understand what he has accomplished. In the new version of the world, there’s one small tweak — no George Bailey. And George discovers that a world without him leads to countless changes, all of them bad, and the delightful little town of Bedford Falls becomes the den of misery and sin known as “Potterville” in honour of the twisted, selfish businessman who owns everything. To put that in the language of chaos theory: Small changes in initial conditions can lead to large changes in outcomes.

But of course the movie only shows the countless ways in which George Bailey’s presence makes things better. That’s why it’s comforting. If you’re a good person and do good work, the movies says, you will make things better.

But it can also go the other way. There’s an episode of the original Star Trek that illustrated this by imagining Spock and Kirk travelling back to 1930s America and saving a woman from being hit by a car. It turns out that in history as it actually unfolded, the woman is struck by the car and dies. And that’s good — because if she had lived, she would have become a major figure in the movement to keep America out of the war, the United States would have stayed neutral, and Hitler would have won. When they figure this out, Spock and Kirk are forced to let the woman die.

It’s not pleasant to think that even something as small as accidentally stepping on a butterfly — to use the image from Ray Bradbury’s A Sound of Thunder — may alter the future in ways we cannot predict. And may as easily be horrible as delightful.

That’s probably why I will not watch that episode of Star Trek on Christmas Eve but I will — randomness permitting — settle down with rum and eggnog and watch It’s a Wonderful Life yet again.

Postscript

If you’re looking for a present for someone who enjoys thinking about thinking, I strongly recommend Duncan Watts’ book Everything is Obvious. It’s so beautifully written, it’s an easy read — and yet it’s intellectually challenging on every page.

A great example of how you never know what will stand the test of time: on one weekend during the summer of 1987, "Spaceballs" and "Dragnet" were released head-to-head, and the winner by a landslide was..."Dragnet." "Spaceballs" wasn't a flop, exactly, but it underperformed during its theatrical run.

Fast forward to 2022, and "Spaceballs" is iconic, while "Dragnet" - despite Tom Hanks and arguably Dan Ackroyd's greatest ever performance - is almost completely forgotten.

The copyright snafu certainly helped (something similar happened to the original "Night of the Living Dead") but "It's a Wonderful Life" might have found its audience anyway. *Many* beloved movies flopped in theaters but went on to become classics. (And then again, some never do. I'm still waiting for people to rediscover "Quick Change" and "The Hard Way," two of the funniest movies of the early nineties and largely unknown.)

Excellent post. As Galen Strawson put it, luck swallows everything. We should be a lot more humble about our successes and others’ failures.