While having a drink with a friend recently, we chatted about fascism.

In years past, I would have added “oddly enough” to the end of that sentence, but it is no longer odd to chat about fascism. One chats about current events, and fascism — unfortunately, incredibly — now falls into that category. (If you disagree, feel free to leave a comment explaining why. I’d love to be convinced fascist currents aren’t swirling in the headlines.)

I shared something in that conversation that, it struck me, you may not know. If not, you will certainly find it interesting. I think it is also contains a lesson that is relevant, even urgent. But you can decide for yourself.

Back in the early 1990s, I did an MA in history, with a focus on fascism and Naziism. So I am reasonably well-informed about Nazis. Including, I thought, the origin of the word “Nazi.”

Germans sometimes take a segment of one or two words and mash them together to create a nickname. So Geheime Staatspolizei (Secret State Police) is GE and STA and PO. Hence Gestapo.

Less sinister is the origin of Adidas. It comes from the name of the company founder, Adolf “Adi” Dassler.

I always assumed this explained “Nazi.” After all, the full name of the party was Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (National Socialist German Worker’s Party.) You can see the NA and the ZI right there. Hence “Nazi.” This also jibed with “Sozi,” sometimes used as a nickname for Socialist.

There is evidence that this apparent conjunction was made in the minds of many Germans and others familiar with Germany, and likely contributed to the spread of “Nazi” as a description of Hitler’s party. But it is not, in fact, its origin.

Its origin is far stranger than that.

According to the Etymologisches Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache, the use of “Nazi” as a label for members of Hitler’s political party was first popularized around 1924 in Bavaria. The timing and location are both significant.

Let’s start with the location.

In Catholic Bavaria (and Austria) the name “Ignatz” (the German form of “Ignatius”) had long been common among rural folk. Or peasants, to use a term appropriate to the era.

Names are commonly turned into diminutive nicknames — think of “Daniel” becoming “Dan” or “Danny” — in most languages, including German. So Bavarians had a diminutive form of “Ignatz.”

It was “Natzi.” Or “Nazi.”

Seeing “Nazi” as a casual nickname is startling to a modern English-speaker, but Spanish has long done something almost identical: “Ignatius” in Spanish is “Ignacio.” And the diminutive of Ignacio is “Nacho” — which has a much happier association in English thanks to Ignacio Anaya, a Mexican who invented the familiar plate of nachos as a dish in 1943 and named it after himself.

Naturally, the clever, educated, urban sorts in Bavaria — like clever, educated, urban sorts most places — saw peasants as ignorant and thick. In American terms, they were yokels. Hicks. Bumpkins. So the clever urban sorts used the nickname common among the peasants — “Nazi” — as a way of calling someone an ignorant and foolish person.

Imagine you are an American today and you call someone a real “Cletus.” We all know, thanks to The Simpsons, that you are calling that person an ignorant, drawling, redneck. In Bavaria, “Nazi” was similar.

Note that this long preceded Hitler and the National Socialists. It had nothing to do with them.

Until around 1924.

Why 1924?

The year before had been disastrous for Germany. It saw devastating hyperinflation. Unrest grew everywhere and the new Weimar Republic looked doomed. Late in the year, a fringe ranter named Adolf Hitler led a band of thugs in an attempt to seize power in Munich, capital of Bavaria, a move known to history as the Beer Hall Putsch. Thanks to incompetent planning and leadership, it was a miserable failure. Sixteen Nazis and four police officers died. Hitler was imprisoned and the party banned.

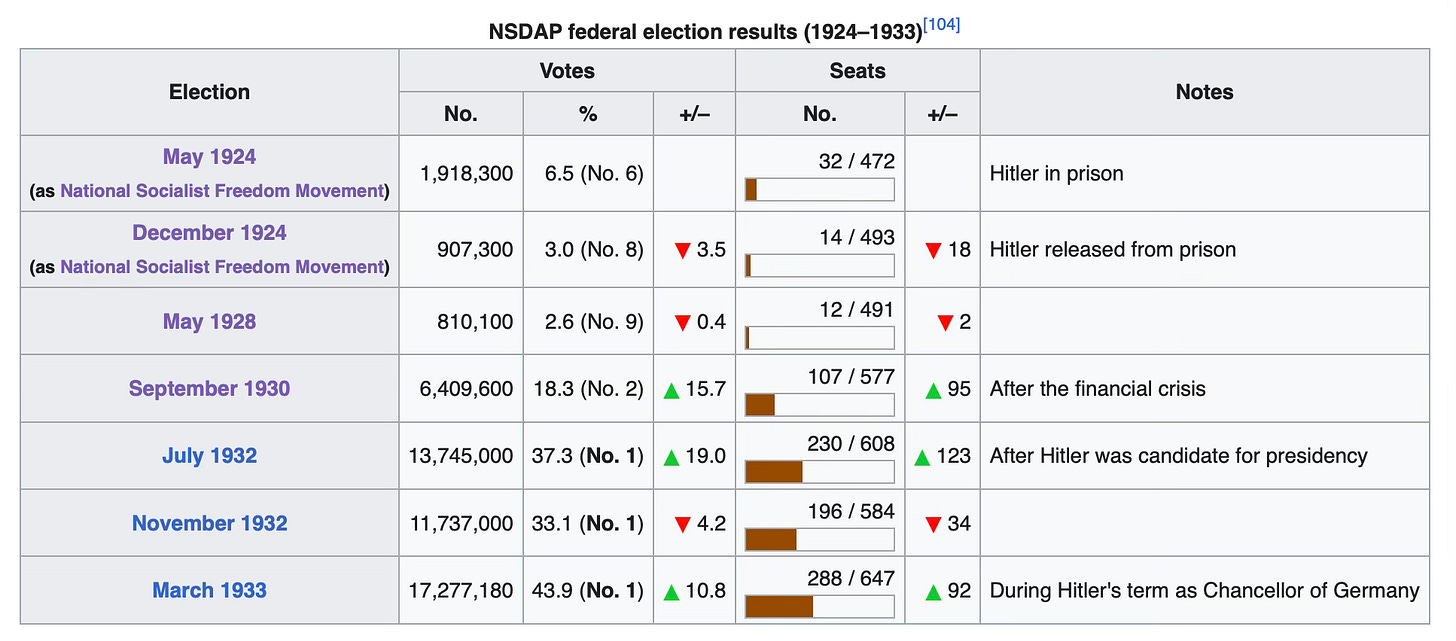

Weimar survived its crisis. In 1924, new currency snuffed out the hyperinflation and conditions rapidly improved. Between 1924 and the end of 1929, Germany prospered, relatively, and its democracy flourished. The ban on Hitler’s party was lifted but the National Socialists were pushed further to the fringe, with Hitler taking a grand total of 2.6% of the popular vote in 1928.

Through this era, clever Bavarians mocked Hitler and his loud, angry, ignorant losers by calling them “Nazis.” That use spread and started to appear in contexts where the slur wasn’t evident and may not have been understood or intended. In 1930, “Nazi” first appeared in The New York Times via reports from Germany. It was still in quotation marks, with the explanation that it meant “National Socialist.”

That year also marked the beginning of the Great Depression, which immediately hammered the Germany economy and exploded unemployment. In September elections, Nazi support soared to 18%, making them the second largest party in Germany. The Nazis finally came to power in 1933 — thanks to President Hindenburg, who richly deserves to have “disaster” forever attached to his surname — and the powerful conservatives who believed they could control Hitler soon discovered how wrong they were.

Did the Nazis call themselves “Nazis”? For the most part, no. There was apparently a brief period in the late 1920s when some attempted to co-opt the word and erase the slur it contained — as gay activists did decades later with “queer” — but they failed. For the duration of Hitler’s time in power, Nazis called themselves “National Socialists,” not “Nazis.” Given the possible double entendre, one would have been well-advised to avoid the word, particularly when it became popular on the BBC and other banned foreign broadcasts.

For the spread of “Nazi” outside Germany, it seems we can thank critics of the new regime, who started fleeing in large numbers soon after Hitler cam to power. Notes the Online Etymology Dictionary: “The use of Nazi Germany, Nazi regime, etc., was popularized by German exiles abroad. From them, it spread into other languages, and eventually was brought back to Germany, after the war.”

That’s some crazy etymology.

But there’s more to this than the long, strange journey taken by an obscure Bavarian colloquialism.

In 1924, and through the remainder of the 1920s, much of Germany saw Hitler and his jackboot-enthusiasts as ignorant, foolish, incompetent, and ridiculous. In a word, they were seen as clowns.

Clowns may be contemptible, but under ordinary circumstances we don’t think of them as dangerous. They’re too incompetent to be dangerous. They are merely, to use the old Bavarian slang, “Nazis.”

But circumstances change. And under the right circumstances, extreme circumstances, some clowns can become very dangerous, indeed.

There are so many clowns in the news these days. Angry clowns. Strident clowns. Clowns who want to make others as bitter and hateful as they are. These clowns bellow their ignorance and strut their incompetence and stumble about like they are wearing makeup and giant red shoes. Any reasonable person who sees them for what they are must laugh. I know I do. Often.

But let’s not be complacent and let laughter obscure what history has shown us so vividly: “Dangerous clown” is not an oxymoron.

Excellent article. Nice to be educated on an early Saturday morning.

Thank you very much. I learned two things--the etymology of the word Nazi and, shamefully for me since I grew up in San Antonio, the origin of nachos. Who knew that Nazis and nachos had the same root? Fascinating, to me, anyway.