Profanity, Past and Present

The evolution of language is all the trickier when words are obscene

You are a mature and serious person. As am I.

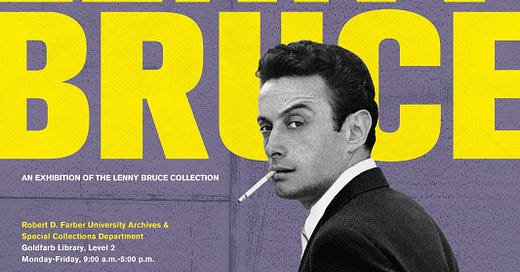

So let us now, together, take a mature and serious look at the following ad, which appeared in American newspapers.

The advertiser is Milton Bradley, the legendary maker of board games and toys.

The ad was published in 1915. The First World War was raging in Europe and the United States was still neutral.

But Americans were following news from the war avidly.

Perhaps you are more mature and serious than I and that ad did not make you snicker. Not even a little giggle. If so, I salute you.

When I first came across it, I guffawed like a 10-year-old boy and took a picture for future reference.

In any event, it is safe to assume that most people reading that ad today have an entirely different reaction from what was intended by the copywriter in 1915. That’s because the most common usage of the word “dick” has transformed over the past century — from a friendly diminutive for the name “Richard” to slang for the penis and an insult inspired by that association.

In the first half of the 20th century, the former was as common as dandelions. There were one or two Dicks in every classroom. Inevitably, a particularly tall Richard would be tagged “Big Dick,” so that phrase appears thousands of times in newspaper archives. But the rise of “dick” as a slur drove the family-friendly nickname to the brink of extinction, and today, in the extremely unlikely event that a Richard arrives at school having been dubbed “Dick” by his father, that father is probably a) absent from his son’s life and b) a fan of the Johnny Cash song “A Boy Named Sue.”

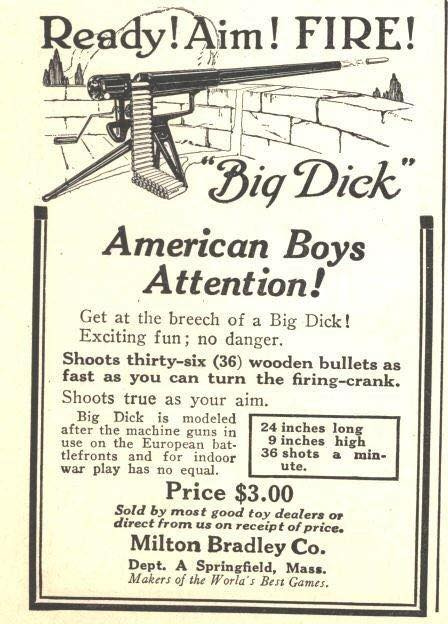

One happy byproduct of the evolution of “dick” is that it makes old newspapers occasionally hilarious.

Consider this little item from 1934.

One can imagine a high school basketball star being called “Big Dick Bradley” today, but only for a significantly different reason.

However, as we established at the beginning, you are a mature and serious person, so I’d better stop the juvenile jokes and get to the point.

There is one. I promise.

The Washington Post recently published a long feature about a collection of brains — 268 in total — in the possession of the Smithsonian. It’s a fascinating story.

Largely at the direction of Aleš Hrdlička, an anthropologist born in 1869 in what is now Czechia, the Smithsonian collected brains drawn from what Hrdlička considered different racial groups and sub-groups. Like most in his line of work in that era, Hrdlička was a eugenicist and scientific racist. But he was far from the worst offender. In fact (and unmentioned by The Post) Hrdlička denounced the most popular form of scientific racism in the first decades of the 20th century, “Nordicism,” which posited that whites were superior to others and various European populations also formed a hierarchy of quality, with north-western Europeans — “Nordics” — being the best.

Hrdlička’s work seems to have had little impact and his brain collection was utterly forgotten. Until now. Which is most awkward. For many years, museums have been trying to make amends for both the racist science and the cavalier treatment of human remains in their past. The last thing the Smithsonian wants today is hundreds of brains collected at the height of scientific racism. But that’s what it’s got.

As I said, fascinating. But — you may ask — what’s this got to do with Big Dick?

It’s in The Post’s note to readers at the bottom of the feature: “To accurately reflect the racism that was common at the time in newspaper articles and official documents, The Post chose to show original records that contain language considered offensive by modern standards.”

The Post doesn’t specify the words that are so shockingly racist they need to justify merely reproducing images of official documents cursed by their mere presence. But on inspection, I see “Negro” and “Laplander.”

That’s it.

“Negro” is definitely a word of the past, and in some contexts would certainly be considered “offensive by modern standards,” but did its use in the past always reflect racism? I suspect the black founders of the Negro National League would not agree. Nor would the black organizers of the Negro World Series. Or… you get the idea. Whether “Negro” — from the Latin “nigra,” for “black” — was offensive depends on who was using it and why. Often, that usage was decidedly not racist. (For more on “Negro” and its far more troubling etymological cousin, read Randall Kennedy’s brilliant book.)

But the Post’s bigger concern, believe it or not, seems to be “Laplander.”

That’s because the Post was able to piece together the story of Mary Sara, a young women living in Alaska who travelled to Seattle for medical treatment. When Sara died of tuberculosis, a physician saw an opportunity to add to the Smithsonian collection — because Sara was a “Laplander,” as the documents put it, an ethnic group native to northern Finland, Sweden, and Norway.

In a caption beneath a photo of a document that describes Sara as a “full-blooded Laplander,” the Post writes, “this undated note describing Mary Sara with a derogatory term was probably written in 1933.”

Maybe the Post is shocked by “full-blooded.” It’s certainly not modern usage. But here, it clearly and simply means “her ethnic heritage comes entirely from this one group.” No need to pass the smelling salts. That leaves “Laplander.”

“Laplander” comes, of course, from “Lapland,” or “Land of the Laps.” The “Laps” were called that by Finns, Swedes, and Norwegians from the South. They called themselves “Sami,” or something close to to it. In recent years, the Sami successfully pushed to make “Sami” common usage throughout Scandinavia (although “Lapland” is still the name of provinces in Sweden and Finland.)

Not surprisingly for a very old word about what was a very distant land, the origin of “Lap” and “Laplander” isn’t clear. Some etymologies suggest the Swedes picked it up from the High German for “simpleton.” Others say it comes from the Finnish word for “periphery” or “edge.” And there are several more possible explanations. But this ancient history is not really why the Sami pushed for change. The reason is more modern.

Eighteenth century colonialism followed by the 19th century rise of nationalism and national identity, were bad for the Sami, as they were for minority native populations around the world. They were marginalized and discriminated against. The words outsiders used to name them were tainted by that subordinate relationship. Changing the language was a way of marking the demanded change in the relationship.

Does that mean that uses of “Lap” and “Laplander” in the past were everywhere and always racist and offensive? Of course not. That entirely depends on who was speaking and why.

That story is remarkably similar to “Eskimo.” In Canada, the “Eskimo” call themselves “Inuit.” In recent years, the Inuit asked for Eskimo to be replaced, and that has almost universally been done in Canada. Even the “Edmonton Eskimos,” a storied football team, are now the “Edmonton Elks.”

Was that because the use of “Eskimo” was everywhere and always racist? Hardly. Like “Lap,” the origins of “Eskimo” are disputed, with some possibilities appearing more offensive to our eyes than others. But what tainted the word isn’t its distant origin in the hazy past. It was the more modern relationship between the Inuit and the white-dominated government and society, which was patronizing and paternalistic at best, arrogant and racist at worst. The name change sprang from a desire to make a break with that and proceed on a more respectful basis.

But none of that means an Edmonton Eskimos fan who shouted “Eskies!!!” in 1953 was expressing the racism in Canadian society. He was probably just happy his team scored a touchdown.

Meanings change. Context is all.

That should be obvious. But it’s not. As the Post footnote shows.

The editors apparently cannot imagine that words “considered offensive by modern standards” could be anything but a reflection of “the racism that was common at the time in newspaper articles and official documents.”

So, we must conclude, if an American in 1933 used the word “Laplander” in a newspaper or official document, that must reflect deep-rooted racial animus toward the Sami people of the northern Scandinavian Peninsula.

Does that make sense? No.

The simpler explanation is that The Post’s editors don’t understand that meanings change and context is all.

I know that sounds outlandish. The Post’s editors are top-tier professionals who work with language. They have to know meanings evolve. They have to know that while “Big Dick” may mean one thing today, it meant something quite different a century ago. (By the way, it’s also at least possible that a “big dick” reference in 1915 could mean a large penis because that meaning was slang as far back as the late 19th century. But it was vulgar and marginal and never heard in polite company, much less newspaper ads.)

But this isn’t any old language we’re talking about, is it? This is language touching on race and racism. Such language is, unfortunately, increasingly treated as its own category, with different rules. “Big Dick” may be funny and illustrative in a discussion about the evolution of language in general; it’s irrelevant if race is involved.

When it comes to race, we tend to treat language not as the endlessly evolving, subtle, living thing it really is. Instead, we treat it as if the letters on the page can always and only mean one thing, and the sounds coming from our mouths must always and only have one effect.

We treat it, in other words, like a magic spell.

Do I exaggerate? The word “niggardly” has nothing to do with the racial slur but it vaguely sounds like the racial slur so anyone with an instinct for self-preservation is well-advised to avoid it. Or anything that even remotely sounds like it. In 2020, a professor teaching a class on business communication discussed “filler words” (empty words such as “like” which people use to fill in spaces) and cited the common Chinese use of “ne ga” (that). The students knew he was using a Chinese word with zero connection to a racial slur. No matter. They were enraged. And the professor was removed. Because that combination of sounds is so powerful that it inflicts great evil no matter the context or intent. Which is to say, it’s a magic spell.

What creature is closely related to a mole?

“Vole.”

What is ‘of’ in French?

“De.”

What is ‘death’ in Middle English?

“Mort.”

Careful. You almost said he-who-must-not-be-named.

Woe betide those who speak the incantation!

Lenny Bruce would have something to say about this.

Bruce famously used profanity on stage — shit, piss, fuck, all the classics — at a time when polite society considered the public utterance of those words slightly more appalling than beating a baby. He was arrested many times. The United Kingdom even barred him from entering the country for fear that he would drop f-bombs like a one-man Luftwaffe.

Bruce didn’t shock for its own sake. And unlike so many comedians today, he didn’t witlessly spew profanity because he was too lazy or dumb to think of something cleverer. He wanted his audience to think about language. Specifically, he wanted them to realize that language only has the meaning we put into it. If we feel the word “fuck” possesses some evil potency, it will. If we don’t, it won’t.

Words are not magic spells. Saying “Voldemort” will not cause the Dark Lord to appear.

That doesn’t mean words can’t wound. Bruce knew better than that. But it does mean we ultimately decide when, or if, words can have that power. We decide.

In one famous/infamous standup routine — much of his comedy was a stream-of-consciousness monologue — Bruce asked if “there are any [n-words] here tonight?” Of course Bruce didn’t say “n-words.” He said the actual [n-word.] (To make his point, Bruce had to use that word. I don’t, so I won’t.)

“What did he say?!” Bruce whispers in mock horror. “Is he so cruel as to say, ‘are there any [n-words] here tonight?!’”

It continues. He repeats [n-word] several times. Then Bruce switches to a rapid-fire delivery of other ethnic slurs, including liberal use of “kike.” (Bruce was a Jew.)

“The point…” he begins, as laughter fades … “If President Kennedy got on television every day and said, ‘I’d like to introduce all the [n-words] in my cabinet,’ and all the [n-words] called themselves [n-words] … And every day all you heard was [n-word] [n-word] [n-word] in the second month [n-word] wouldn’t mean as much as ‘goodnight’ or ‘God bless you’ …. [N-word] would lose its impact and it would never make any poor little [n-word] cry when he came home from school.”

The taboo gives the word power. If the taboo goes, so does its power.

I’m not endorsing how Bruce made his point. And I think Bruce radically underestimated how hard it is to erase a taboo, particularly one with a history as deep and hurtful as that word. But the basic idea? It’s correct. Words really can evolve from vicious to benign. Or in the opposite direction. And evolutions like these are driven not by mutation and random selection but by us. We choose.

Bruce’s persecution and what followed his death in 1966 demonstrated exactly that.

Bruce was the cutting edge of a counterculture that deliberately used profanity casually. Saying words like “shit” in public was a way of proclaiming yourself a hipster, a rebel, someone who wouldn’t conform to foolish social conventions and wanted to shake things up.

In 1970, the word “fuck” was heard for the first time in a major motion picture. That movie was M*A*S*H and the word was heard precisely once. In 1972, George Carlin brought the house down — but not society — with his “seven dirty words” routine. “These words have no power,” Carlin observed. “We give them this power by refusing to be free and easy with them. We give them great power over us. They really, in themselves, have no power.”

In the decades since, the taboo on Carlin’s “seven dirty words” has greatly diminished. They’re still not entirely respectable and I don’t expect to hear politicians drop f-bombs anytime soon. But they are commonplace. Hack comedians who drop f-bombs in every sentence don’t shock today. They bore.

Lenny Bruce was right.

That said, there have always been proscribed words, and there always will be, because proscribed words serve a need. When we are outraged, or shocked, or running for cover, we do not reach for words whose literal meanings express information we wish to communicate. We shout “fuck!” in a raw explosion of emotion. And if “fuck” is ultimately drained of all its taboo power, we’ll find something else. Because there’s always something else. My favourite illustration is the classic Quebecois curse: “tabarnaque!” It literally means “tabernacle” but translated into English it becomes “shit!” or “fuck!” So why is it a curse? Quebec was a deeply religious society. To say “tabernacle” this way was once far more transgressive than referring to a bodily function or act. Quebec French is littered with such gems.

“What a society considers profane reveals what it believes to be sacrosanct,” observes linguist John McWhorter.

That’s why another observation of McWhorter’s is so important. As the taboo power of the older profanity has waned, group slurs — racial, ethnic, gender, and sexuality — which were once at least somewhat acceptable in public were proscribed. This was a sweeping victory for the counterculture, arguably its biggest and most complete.

As a result of this transformation, I can make jokes about big dicks in this essay without fear of causing a flood of cancellations.

I can say “damn” almost anywhere. I can say “shit” in university lecture halls. I can even say “fuck” next to a police officer in Trafalgar Square and not be arrested.

But I can’t say “Eskimo” or “Laplander” without compelling reason — such as writing an essay about the evolution of those terms — and not expect at least some push back. And, as a white man, I can’t say [n-word] under practically any circumstances, unless I want to live the rest of my days alone in a cabin in the woods.

Is that progress? Think of it as a trade. We diminished the profane power of words related to body parts and bodily functions. In exchange, we proscribed a bunch of other words tainted by long association with discrimination and hate in the hope that doing so would ease the hurt of historically marginalized peoples. Sounds like a good swap to me.

But if we have drained much of the power from the seven dirty words, should we not, as Bruce suggested, do with the same with group slurs? It can be done. “Queer” is proof of that. It was long a slur for homosexuals so activists deliberately appropriated the word. Eventually, it lost its sting. Then it became a point of pride. That’s an astonishing evolution.

But that evolution didn’t take the one month Lenny Bruce mentioned. It took decades. So any attempt to detoxify a word this way should be decided and led by the people who are hurt by it. If the Inuit would rather we simply replace Eskimo with Inuit, that’s fine. No great loss. [N-word] is orders of magnitude worse but the same principle, it seems to me, should apply. (Which is why I’ve observed that taboo in this column.)

All that said, we seem at risk of losing the essential insight of Lenny Bruce and George Carlin. We may now socially proscribe group slurs, and that may be a good thing, but they’re still only words. They’re not magic spells. They don’t have one, awful meaning fixed for all time.

Etymology is complicated. So is history.

But people aren’t stupid, fortunately. They can easily grasp the difference between the big dicks of 1915 and 2023.

And understand that language evolves.

PS: Want to buy a Big Dick? There’s one for sale on eBay for a mere $1,000.

PPS: The closest analogue to the modern “dick” is likely the Yiddish loan-word “putz.” It means a fool, or, vulgarly, a penis. I discovered this etymology when I called someone a putz in my newspaper column and a rabbi was so kind as to send a note saying, “are you aware that…?”

I was not, rabbi. Many thanks.

Interesting story. I’d never heard of that game, happily. Growing up in northern Ontario in the 1970s, that word was almost nonexistent. The only instance of it I can recall was in eeny meeny miny mo -- the random selection rhyme -- which used it in the original but was replaced with “tiger.” I seem to recall that we understood it was a bad word but not why.

You could do schmuck as another P.S. -- Schmuck, or shmuck, is a pejorative term meaning one who is stupid or foolish, or an obnoxious, contemptible or detestable person. The word came into the English language from Yiddish (Yiddish: שמאָק, shmok), where it has similar pejorative meanings, but where its literal meaning is a vulgar term for a penis.