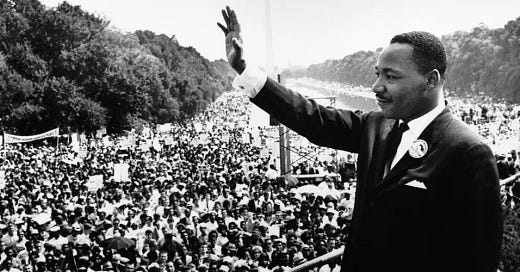

On the Martin Luther King Day just passed, I learned something about King that’s interesting on multiple levels:

In 1958, when Martin Luther King Jr. was 29 years old, he wrote an advice column in Ebony, a black magazine. In one column, an anonymous boy or young man — his age isn’t clear — asked King for advice. Following is the question and King’s response. (The full document is available here.)

Question: My problem is different from the ones most people have. I am a boy, but I feel about boys the way I ought to feel about girls. I don’t want my parents to know about me. What can I do? Is there any place where I can go for help?

Answer: Your problem is not at all an uncommon one. However, it does require careful attention. The type of feeling that you have toward boys is probably not an innate tendency, but something that has been culturally acquired. Your reasons for adopting this habit have now been consciously suppressed or unconsciously repressed. Therefore, it is necessary to deal with this problem by getting back to some of the experiences and circumstances that lead to the habit. In order to do this I would suggest that you see a good psychiatrist who can assist you in bringing to the forefront of conscience all of those experiences and circumstances that lead to the habit. You are already on the right road toward a solution, since you honestly recognize the problem and have a desire to solve it.

There are two ways to read this exchange.

The first is through the lens of the present: This is a young man expressing homosexual desire and King tells him he is sick. See a psychiatrist, King advises. You can be cured.

There are still people who think like this today and they are rightly reviled for it. In fact, in some jurisdictions, what King wrote could be illegal. Canada, for example, recently passed a law making it a crime to cause someone to undergo “conversion therapy.”

Seen through this presentist lens, what King did was appalling. Many people have been “cancelled” for less.

But King wasn’t born in 1994 and writing in 2023. He was born in 1929 and writing in 1958. That historical context is the second lens through which we can read King’s advice.

In 1958, gay sex was almost universally criminal across the United States. There was no gay rights movement. Gay people were almost never openly gay in mainstream society because they faced profound social stigma. To be gay was to be sick, perverted, disgusting. Hatred and fear of homosexuality were so common that it was physically, financially, and reputationally dangerous to be openly gay. The federal government barred the employment of any homosexual on the grounds that they were at grave risk of blackmail, and thus were security threats. Thousands of people lost their jobs in this “lavender scare.”

That is the world in which King lived and wrote his words. And that context completely changes how we read King’s advice:

King does not condemn the young man. He doesn’t express disgust. He simply says, in gentle terms, that the young man has a “problem.” He then offers reassurance. “Your problem is not at all uncommon,” King writes. He gives a little praise. “You are already on the right road toward a solution….” And he offers hope. “I would suggest that you see a good psychiatrist who can assist you….”

In the context of 1958, this is an unusually generous, humane response.

So how should we, today, feel about what the great civil rights leader wrote?

Of course his thinking and words are unacceptable today. But do they change how we judge Martin Luther King Jr.? Do they make him a bigot we should revile? Should we stop honouring the man?

Before I answer that, I’ll add a more important reference point.

A man named Bayard Rustin was a close and influential advisor to King in the civil rights movement.

Rustin was a rare and brave figure: He was openly gay despite having repeatedly suffered for refusing to hide his sexuality. But King was fine with that. Rustin was a superb organizer and King trusted his advice.

But that didn’t last. People around King warned him that Rustin was a liability. He could be used against the movement. King reluctantly agreed. Rustin was forced to resign.

Again, there are two ways we can see this.

Looking through a presentist lens, King fired a trusted assistant because he was gay. That is outrageous and shameful.

But in historical context? King showed himself to be remarkably open and tolerant. Only when Rustin’s sexuality clearly became a liability to the cause they both served did he, with regret, fire him.

Again, what would be open-and-shut odious behaviour in 2023 looks quite different in historical context

I doubt anything I’ve written here is controversial in the least.

In fact, I learned of King’s advice to a young gay man in 1958 via a story published on MLK Day by PinkNews, a UK-based LGBT publication. That story did not condemn Martin Luther King. To the contrary, it strongly emphasized the historical context and concluded that the exchange was actually to King’s credit.

Despite this, the civil rights hero was able to speak to and about gay people with a level of patience and kindness that was unusual for his time….

Though Dr King’s response would be troubling by modern standards, his advice to the boy is remarkably calm and polite given the fears and active scaremongering about gay people at the time.

I think that’s exactly right. To condemn King for not thinking and acting as if he were living in 2023 would be unfair, even absurd.

And I think most or all reasonable people would agree.

But this is Martin Luther King Jr. we’re talking about! There are few historical figures as admired and praised today. It’s not too strong to say that King is widely venerated.

To apply historical context and exonerate King is emotionally satisfying. It keeps our perceptions and judgments nicely aligned. It would be so much harder to think that this secular saint said and did things we find morally appalling.

But when it comes to other historical figures — particularly those we feel no affection for — it’s another matter entirely.

Just consider the controversy around NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, which I wrote about last week.

James Webb was the head of NASA during the critical years of the 1960s and a top State Department employee in the 1950s. These key years almost exactly overlapped with Martin Luther King’s career in the civil rights movement.

Webb stands accused of anti-gay bigotry. But what did he do, exactly? I set out the indictment in that essay. I think it’s fair to say that his offences on this score are no worse than those of Martin Luther King Jr’s. And the historical context is precisely the same.

But for the many people demanding Webb’s name be removed from the telescope, historical context doesn’t save him. He offended the moral standards of 2023 so he’s got to go.

The contrast between the treatment of King and Webb is an extreme example but this sort of double-standard is depressingly common in debates about statues and other public honours.

When taking historical context into account supports the conclusions people wish to reach, they take historical context into account. When it doesn’t, they don’t.

There’s a monument to this motivated reasoning in Ottawa: At a time when historical figures who had any involvement with slavery are condemned and their names removed from public honours, not a peep of protest has been raised about a prominent statue next to Parliament Hill that honours a military leader who was also one of the biggest slavers in Canadian history. This man even has a city named after him — again, without controversy. That’s because Joseph Brant was a Mohawk chief, not a British aristocrat, and nobody wants to strip honours from an indigenous historical figure. So…historical context…mumble, mumble…let’s move along.

Reasonable people will often disagree about who and what we honour in public. That’s fine. We may also disagree about what the relevant historical context is, and what it says about historical figures. That’s fine, too. (I’ll write more about the use of historical context in future.)

But double standards are indefensible. Historical context is always relevant. It must always be considered seriously.

If it is absurd to condemn Martin Luther King Jr. for writing words that were unusually humane for his day — I trust we’re all in agreement that it is — it is just as absurd to tear other historical figures out of their time and place and condemn them for the crime of failing the moral standards of a time and place they never knew.

I wish I had written this or at least had the opportunity to use this in my classes. You have more than gratified and impressed this former history teacher and for that I thank you!

Historical context IS everything, not just for historians. Think Tchaikovsky, Shakespeare, Leonardo da Vinci .... on and on ..... mumble mumble