It’s Sunday, so here’s a smörgåsbord of observations, links, and whatnot.

First up, “soft seat or hard seat?” A delicious anecdote from H.V. Kaltenborn.

“Who?” you ask.

In the first three decades of the 20th century, H.V. Kaltenborn was the top foreign affairs correspondent for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, a newspaper with considerable readership and clout a century ago. Kaltenborn was also one of the first pundits to work in radio. In 1930, CBS made him a full-time radio news correspondent and all through the tumult of the 1930s, he was the most prominent voice in America trying to make sense of the rise of fascism and the slide into war. The legendary Edward R. Murrow called him the “dean” of radio commentators.

But he is almost entirely forgotten today. Sic transit gloria mundi, as they say.

As regular readers know, I am studying the early histories of various technologies, including radio, so I recently got a copy of Kaltenborn’s autobiography. (It turned out to be signed. I was thrilled. Which, as I explained a while back, is unusual, as I tend to think of signatures as graffiti and a signed book as a vandalized book. But Kaltenborn is long-dead and long-forgotten, and for some reason that makes having his signature exciting to me. Go figure.)

It’s a surprisingly interesting read, not least because Kaltenborn was remarkably well-travelled in an era when getting around the world took a great deal of time and money.

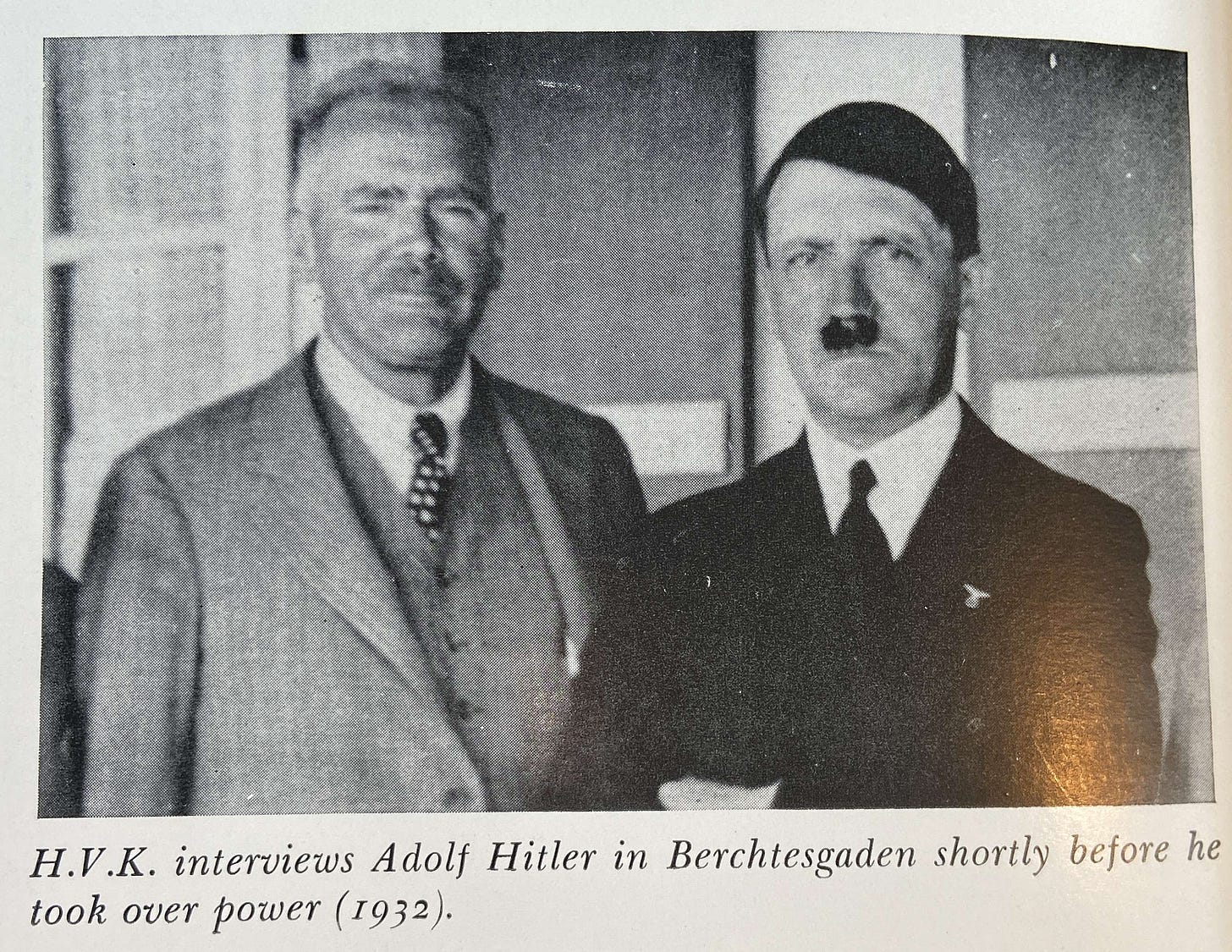

Here he is in 1932 with an up-and-comer in German politics:

As you might expect, Kaltenborn’s book is stuffed with revealing vignettes. His comparison of Hoover and Roosevelt, in public and private, is fascinating. (He concludes that Hoover largely lacked the personal skills and willingness to horse trade that helped make Roosevelt such a success.)

But the anecdotes from his travels are the book’s real gems.

Ever since the Russian Revolution, I had been eager to visit Russia and see the Communist experiment at firsthand. In the summer of 1926, I applied for a visa. It was not hard to get. Few newspaperman were stationed in the country. The only visitors were either businessman, engineers or social science students interested in the Communist experiment. The violence of the revolution and the unsettled conditions deterred others.

I entered Russia through Finland, and my first contact with the Communist way of life came at the border. Because of the mutual suspicion and hostility between Russia and Finland, it was impossible to buy a through ticket to Leningrad. After the train crossed the no-man's land between the two countries, I had to leave the single coach on which I crossed over as the only passenger and buy a Russian railroad ticket to Leningrad at the Russian station.

“How much for a first-class ticket to Leningrad,” I asked. The ticket clerk looked at me coldly and snapped back, “we have no classes on the Soviet railroads.”

I tried again. “Please give me a ticket to Leningrad.” That mollified the agent.

“How will you have it?” he asked. “Soft seat or hard seat?”

After buying myself a soft seat ticket at three times the cost of a hard seat, I found that the soft seat cars are much like the second class cars in European railways. The hard seat cars were extremely dirty and had wooden benches as seats. I soon learned that in the classless Soviet Union there are many unacknowledged class distinctions.

“Soft seat or hard seat?” is my new favourite shorthand for ideologically loaded language whose purpose is dishonesty.

Given the state of popular discourse, I expect to use it a lot.

Next, what hath Superforecasting wrought?

When Phil Tetlock and I wrote Superforecasting, we hoped — but did not forecast — that it would inspire major organizations to finally get serious about the forecasts they made and used.

It is ridiculous that governments and corporations pay enormous amounts of money for forecasting whose accuracy isn’t at all clear. It’s worse that they use this forecasting as the basis for important decisions. And it’s downright ludicrous that they aren’t interested in figuring out if they can improve that forecasting and make better decisions.

Phil’s research program, as we described in Superforecasting, is heavily supported by the US intelligence community’s efforts to do better on all these fronts. Why wouldn’t other organizations follow suit?

To date, these hopes have only been realized modestly. Some organizations — particularly on Wall Street — really took to the message to town. But these organizations tended to be those that were already more serious about these matters and therefore the organizations that least needed to do this. Conversely, organizations that were hopeless have proven to be … hopeless. The worst is the news media.

Every day, the news is full of pundits tell us what will and won’t happen even though neither the pundits nor those who employ them have any clue how accurate their forecasting is. And even less interest in finding out. When Superforecasting was released, we couldn’t even interest the media in op-eds about forecasting and how to improve it. The status quo works well for them and they have not the slightest interest in unsettling it, even if the product they are providing their customers now is of dubious quality and it could be a lot better with a little effort. As a long-time journalist, I find that unprofessional, at a minimum, and downright shameful in some cases.

But in happier news, the government of the United Kingdom has launched a major project to do exactly what Superforecasting advises.

It goes by the wonderfully exotic name of “Cosmic Bazaar.” I won’t summarize it here as Andy Owen has done that and I am lazy. But please have a look at Andy’s post. And if you happen to be someone with some pull in your organization, give it a close read and seriously consider whether you can do something similar.

An aside: When “Cosmic Bazaar” was scheduled to launch in the spring of 2020, the program’s leadership asked me to give a keynote on the morning of April 8th in London. April 8th happens to be my birthday. The location was just down the street from the British Museum. So I was going to spend most of my birthday wandering the British Museum, followed by a late-afternoon pint or three in an English pub. Add a hockey game and that is a complete description of what every day in my personal heaven would be. I’ve never more looked forward to a trip.

Then came Covid. Heaven would have to wait.

So what I’m saying is: Please, someone in the UK, invite me to give a talk somewhere within walking distance of the British Museum. I can be flexible about the date. And I’ll buy the beer. Thanks so much.

Now, what the Sears catalogue tells us about building houses.

For most of the first half of the 20th century, anyone could open the Sears catalogue and order a home.

From plans to material, everything you needed was delivered. All you had to supply was the labour.

And these homes weren’t junk. By the standard of the time, they ranged from solidly middle class to the sort of home an upper-middle class lawyer would be proud to own.

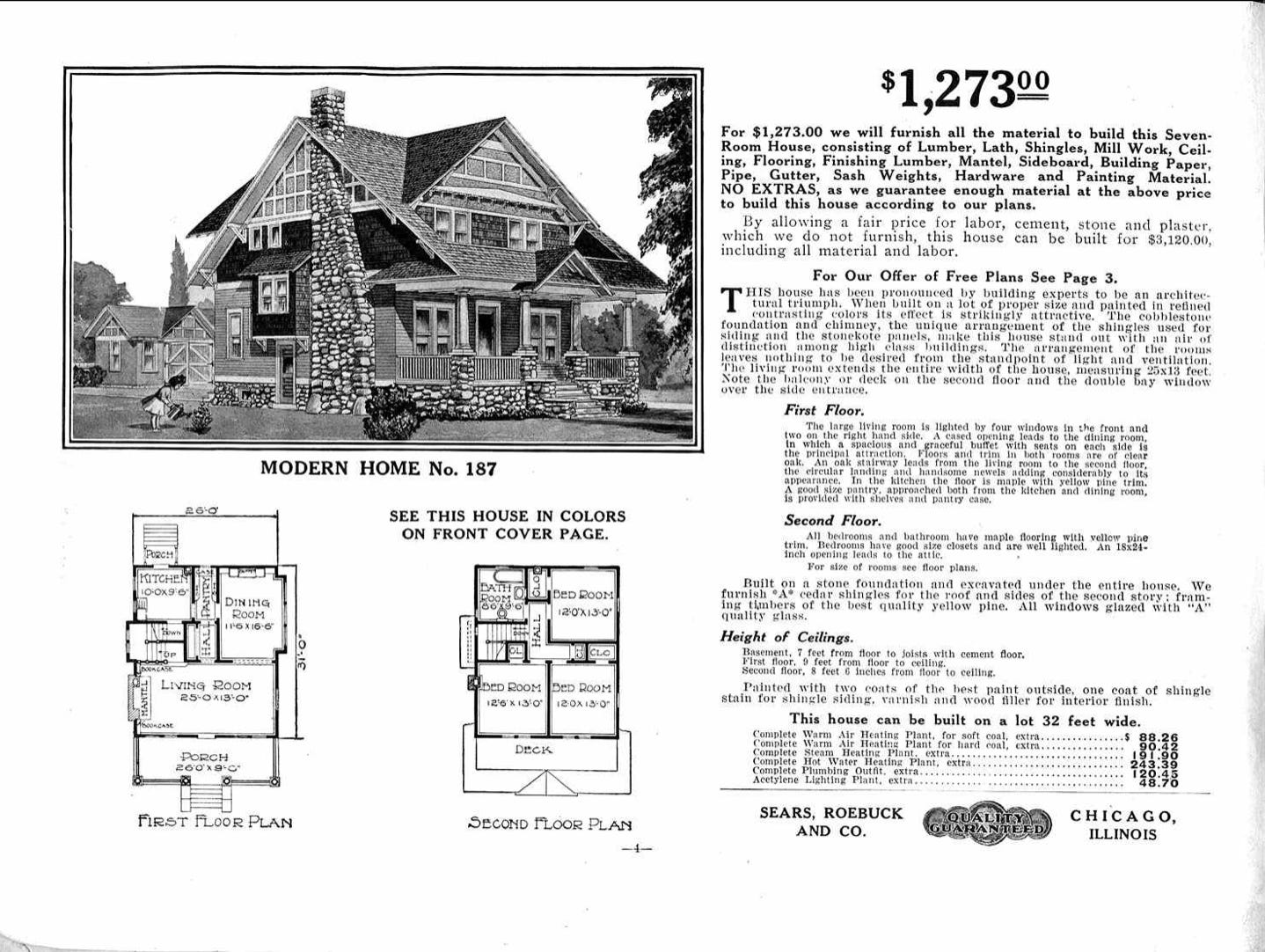

Have a look at this beauty from 1913:

Price of plans and materials: $1,273. Total estimated cost of building this home, including labour: $3,120.

Of course those figures aren’t adjust for inflation, so allow me to make those calculations. Cost of plans and materials: $38,469. Total including labour: $94,284.

It’s important to note that plumbing, wiring, and heating weren’t included. Labour was a lot cheaper a century ago. And many of the materials would not be as good as they are today.

But still. Arbitrarily quadruple that price and you get $153,876 (without labour) and $377,136 (all-in). For a quite lovely new home.

And if you were wondering, yes, the quality was high. In fact, lots of these homes are still around today and they are highly desirable. Here’s a Bob Villa episode involving one. And here is a feature about the Sears homes that includes both contemporary drawings and photographs of homes that are now 80, 90, 100 years old and older.

Bent Flyvbjerg and I mention the Sears catalogue homes in the final chapter of How Big Things Get Done, where we discuss how modularity can lower costs, boost speed, and cut risk. Because “modular” is what these factory-made, site-assembled homes were.

Today, “modular home” is all but synonymous with cheap crap thanks to decades of modular homes that were, in fact, cheap crap. But there is absolutely no reason why modular homes can’t be much more than that. And lots of smart people are working on making that happen.

Officials in the many regions and countries struggling to provide affordable housing should really consider opening a century-old catalogue.

And speaking of How Big Things Get Done…

If you want to discuss absolutely anything related to my new book with Oxford University Professor Bent Flyvbjerg, please share on this thread.

If you want to learn more about the book — like how to buy it, amirite? — have a look here.

Lastly, over on LinkedIn, Bent and I asked people to share their personal experiences with project planning and delivery. Write something interesting and you can win a Zoom call in which Bent and I will talk about whatever you want to talk about, with you alone or with you and your work team.

Apparently Sears offered “soft seat” options such as a hot water heating plant back in the day

The house I grew up in is an Eaton's Catalogue house built in 1917. The whole package was shipped to the local train station and the local builder put up the house.