When I asked readers to nominate golden years in the past when life was good and free of fear — to illustrate hindsight bias and the uncertainty illusion — I expected you to pick a year in the 1990s. You did. And more than one. I also expected a year in the 1980s. For some reason, you didn’t, which was most disappointing since I was hoping to riff on Oprah Winfrey warning in 1987 that one in five heterosexual Americans could be dead of AIDS within three years, how Japan was going to buy the United States and keep Americans as pets, and the most depressing television show ever to appear on American televisions.

I expected I would not hear nominations from the 1970s, however. Even half a century later, the 1970s are popularly remembered as the decade of disco and bad haircuts, which is better than the Dirty Thirties but a long way from a worry-free golden age.

But still I got two nominations from the 1970s — 1972 and 1976.

One way to see the 1970s is that it was a couple of good years bookended between white-knuckle fear.

On one side was the end of the long post-war boom. It was an era of race riots and soaring crime, choking pollution, the shocking defeat of the United States in Vietnam, the American abandonment of the gold standard (which would lead to hyperinflation and economic collapse, according to gold bugs), a White House scandal that shook confidence in American governance, an oil crisis that threatened the energy foundations of the developed world, lineups to get gas (when the pumps weren't empty), plus a combination of low growth and high inflation (“stagflation”) which economists had thought was impossible. No holiday from history there.

I wrote a little about this era in Future Babble, noting the work of Robert Heilbroner. Today, Heilbroner is remembered only as the author of The Worldly Philosophers, a collection of biographies of the famous economists which was a best-seller when it was first published in 1953 and is still in print. But Heilbroner was also a socialist and popular writer much read in the 1970s. In 1974, he published in An Inquiry Into The Human Prospect, which distills the vibe of America’s intellectual class in that grim year.

The mood was one of “puzzlement and despair,” he noted. “There is a question in the air, more sensed than seen, like the invisible approach of a distant storm, a question I would hesitate to ask aloud did I not believe it existed unvoiced in the minds of many: ‘Is there hope for man?’” Like a god standing at the crest of Olympus, Heilbroner gazed across history and the globe and rendered his verdict: Not really. “The outlook for man, I believe, is painful, difficult, perhaps desperate, and the hope that can be held out for his future prospects seems to be very slim indeed. Thus, to anticipate the conclusions of our inquiry, the answer as to whether we can conceive of the future other than as a continuation of the darkness, cruelty, and disorder of the past seems to me to be no; and to the question of whether worse impends, yes.”

Translation: We’re f***ed.

The reasons Heilbroner despaired included food shortages, inflation, environmental degradation, resource depletion, the decline of democracy, the rise of strong-man governments, and nuclear brinksmanship. Toss in pandemics and Donald Trump and Heilbroner’s worries have a certain contemporary feel.

But Heilbroner didn’t think it was the end of the world.

“The human prospect is not a death sentence. It is not an inevitable doomsday to which we are headed, although the risk of enormous catastrophes exists.” It’s more like “a contingent life sentence – one that will permit the continuance of human society, but only on a basis very different from the present, and probably only after much suffering in the period of transition.” Unfortunately, that new basis would be brutal authoritarianism in the United States and other developed countries because only such governments would have the strength to see us through the dark days ahead. These new regimes would feature a government that “blends a ‘religious’ orientation with a ‘military’ discipline,” Heilbroner wrote. The closest thing to it was China under Mao Zedong. “Such a monastic organization of society may be repugnant to us,” Heilbroner wrote with some understatement, “but I suspect it offers the greatest promise of making those enormous transformations needed to reach a new stable socio-economic basis.”

So that was the human prospect: Maoist China or extinction.

That’s not good.

And “not good” was exactly the phrase President Gerald Ford used in his 1975 State of the Union address.

I want to speak very bluntly. I've got bad news, and I don't expect much, if any, applause…. I must say to you that the state of the Union is not good.

“My fellow Americans, everything sucks,” is not the sort of thing American presidents say in good years. Or middling years. So I trust I have established that the widely felt mood of the first half of the 1970s was not altogether happy.

The other bookend, at the close of the 1970s, was even grimmer, as most of the preceding trends worsened. Another energy shock. Britain’s “winter of discontent.” In 1979, Jimmy Carter delivered a prime-time speech that is probably the darkest ever delivered by an American president in peacetime. Or in wartime, for that matter.

“I had planned to speak to you about an important topic – energy,” Carter said solemnly to a television camera. It was July 15, 1979. The president sat at the big desk in the Oval Office. “For the fifth time, I would have described the urgency of the problem and laid out a series of legislative recommendations to the Congress. But as I was preparing to speak, I began to ask myself the same question that I now know has been troubling many of you. Why have we not been able to get together as a nation to solve our serious energy problems? It’s clear that the true problems of our nation are much deeper – deeper than gasoline lines or energy shortages, deeper even than inflation or recession.”

It goes downhill from there.

While the threats of energy shortages and inflation were serious, the “crisis of confidence” threatens “the very heart and soul and spirit of our national will,” he said. “The erosion of our confidence in the future is threatening to destroy the social and the political fabric of America.”

The signs were all around. “For the first time in the history of our country a majority of our people believe that the next five years will be worse than the past five years. Two-thirds of our people do not even vote. The productivity of American workers is actually dropping, and the willingness of Americans to save for the future has fallen below that of all other people in the Western world. As you know, there is a growing disrespect for government and for churches and for schools, the news media, and other institutions. This is not a message of happiness or reassurance, but it is the truth and it is a warning.”

In sum, 1979 was a downer.

And yet, right there in the middle of the 1970s you can, indeed, find a few years with strong economic growth and falling unemployment. And 1976 — twelve months after the president said the state of the union is “not good” — is the best of these.

But it was no oasis. The gloom of the earlier and later years hung over 1976 like smoke.

Consider the low-budget movie from an unknown writer and star that won multiple Oscars and was by far the top draw at the box-office in 1976: Sylvester Stallone’s Rocky is about a once-promising boxer who is a bedraggled loser until he gets a lucky break, rediscovers American grit, and goes the distance. Stallone credited the gloom of the era for the success of a movie that he deliberately wrote to be an old-fashioned appeal to people losing faith. Rocky doesn’t even win, but he proves he isn’t a bum, and that was good enough in 1976. Audiences stood and cheered at screenings.

Or consider another prime-time speech Jimmy Carter gave (in early 1977, so I’m cheating slightly, forgive me). The president actually told Americans things appeared better than they were, so don’t get your hopes up.

“Tonight, I want to have an unpleasant talk with you,” Carter began in his inimitable style.

“[This is] a problem unprecedented in history. With the exception of preventing war, this is the greatest challenge our country will face during our lifetimes. The energy crisis has not yet overwhelmed us, but it will if we do not act quickly.”

It’s the end of the world, people. Please pay attention.

“I know that some of you may doubt that we face real energy shortages,” Carter said. “The 1973 gasoline lines are gone, and our homes are warm again. But our energy problem is worse tonight than it was in 1973 or a few weeks ago in the dead of winter. It is worse because more waste has occurred, and more time has passed by without our planning for the future. And it will get worse every day until we act.” Petroleum must cease to be the foundation of the American economy.

Conservation was the top priority. There must also be huge increases in solar energy and coal production. And “we must start now to develop the new, unconventional sources of energy we will rely on in the next century.” It was a huge effort, Carter warned – the “moral equivalent of war.” It would require sacrifices. But it had to be done. “The alternative may be national catastrophe.”

Thanks, Jimmy. You always bring the fun. (Actually, people did have a good laugh when the president’s critics pointed out that the stirring phrase “moral equivalent of war,” which he pinched from a 1906 essay by William James, produced the unfortunate acronym “MEOW.”)

So, yes, 1976 was better than the years alongside it, but that is damning with faint praise.

Robert Heilbroner illustrates the point: In 1976, he published another book about humanity’s prospects and it was much less gloomy than his 1974 opus. Rather than Maoist China or extinction, Heilbroner forecast the end of capitalism (good!), the end of growth (bad!), and the end of freedom (really bad!).

Gerald Ford was not a man habitually inclined to eloquence but facing an election later that year — and the need to get a lot cheerier in a hurry — he neatly summed up the situation in his 1976 State of the Union address:

Just a year ago I reported that the state of the Union was not good. Tonight, I report that the state of our Union is better--in many ways a lot better--but still not good enough.

In 1976, people widely agreed that President Gerald Ford was a decent man. And they agreed that 1976 was better than 1975. But Ford still lost. It was that kind of year.

Postscript

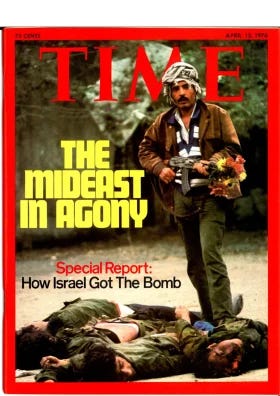

Some day I’ll write a PhD dissertation using nothing but Time magazine covers.

Here are two from 1976.

The first is one of those scary stories that comes, causes a splash, and goes without leaving a trace in memory — thus contribution to the sense that we worried so much less in the past.

From the July 12, 1976 issue:

Now, however, all over the U.S. and in many areas around the globe, bugs are on the march, relentlessly not only retaking the ground so recently won by Homo sapiens but also making new advances. Aided by Government restrictions on pesticides as well as their own growing immunity to the chemicals, and benefiting further from the miscalculations and complacency of their human enemies, insects seem well on their way to fulfilling the chilling prophecy of The Hellstrom Chronicle: "If any living species is to inherit the earth, it will not be man.

The opposite sort of cover is the Eternal Story. This one was published April 12, 1976, although it could have appeared any day since, oh, 1948 or 1914.

Finally, a trivia question:

If, in 1976, Rocky was the top-grossing movie in the United States, what was number two?

Give up?

Astonishingly (at least to me) it was a documentary called To Fly! which is a brief look at the history of flight. The secret of its success? It is full of aerial shots and was presented at the Smithsonian on a new IMAX screen. And it was a sensation, propelling the creation of more IMAX screens.

Yes, it is on YouTube.

I have to throw in a comment, without reading (most of) the article. It was my high-school grad year, and it's hard to see a year badly through that lens of youth. But my comment is because the article pretty much doesn't apply to my life in Calgary, Canada, which was the 1970s/1980s "Upside Down".

When the rest of the continent groaned under massive recession caused by a 500% increase in the world price of oil, Calgary was delivering that oil - growing at a staggering rate, for an already-large city. Everybody who could do anything useful had a job, and wages kept going up. My high-school friends thought me mad to go into University, there were so many good construction jobs at high wages.

Then the 1980s were a decade of pain, poverty and shame for Calgary, when the price of oil fell, all the contracts ended, there were 5 pages of "dollar sales" of underwater mortgages in the Calgary Herald. The population dropped for the only time in in its history, in 1982, and the houses were down 25%. 90% of my engineering firm was laid off.

Imagine our dropped jaws and clenched fists at Reagan running on "are you better off now" in 1984. Everybody else's cheap-oil, end-of-recession joy was our lost houses.

So, picking a "best year", man, is a VERY, VERY local decision, for some localities.

True! For a new arrival from India, fleeing suspension of civil rights by Indira Gandhi’s ‘emergency’, Canada, Quebec, Montreal all seemed peaceable, and problems appeared or were navigable.