The standard summary of the road to the Second World War goes like this: In the 1930s, fascists launched invasions which other governments failed to punish with tough economic sanctions and diplomatic isolation. The fascists learned they could profit from war, encouraging more aggression. This escalation continued until Germany invaded Poland, and Britain and France were finally forced to declare war.

The first step in the long march to the worst war in history came in September, 1931, in the Chinese province of Manchuria.

Radicals in the Japanese army, acting on their own initiative, blew up a section of railway Japan had built in Manchuria, which bordered on the Japanese colony of Korea. On the pretext that Japan had been attacked, the army seized control of Manchuria.

For Europeans and Americans, Manchuria was an obscure, distant region made all the more irrelevant by the Great Depression that was ravaging economies around the world. The last thing Western governments wanted to deal with was a thorny conflict in a place their unemployed voters couldn’t find on a map.

American President Herbert Hoover refused to even consider economic sanctions. He said it would be like “sticking pins in a tiger.”

But a handful of statesmen looked at the previous half-century of conflict and realized that if Japan were allowed to profit from aggression it would encourage further aggression and ultimately endanger international peace. They pushed the League of Nations to impose sanctions. But without American backing, the League balked.

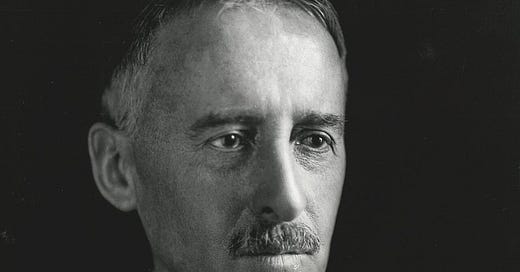

One of those far-sighted statesmen was US Secretary of State Henry Stimson.

Henry Stimson was one of the greatest statesmen America has ever produced.

He was Secretary of War under Republican President Howard Taft (1911-1913). Then Secretary of State under Republican Herbert Hoover (1929-1933). And finally, in 1940, when Stimson was 73 years old, Democratic President Franklin Roosevelt made him Secretary of War again. At the time, the United States was frantically strengthening its tiny military and Stimson supervised its transformation into an immense global force. Roosevelt died shortly before victory in Europe but his successor, Harry Truman, kept Stimson in office. Only when Japan surrendered did Stimson finally take his well-earned retirement. He was 77 years old.

In 1931, as Hoover’s Secretary of State, Stimson understood that allowing any country to profit from invasion, anywhere, would eventually endanger the world.

Blocked by Hoover from applying sanctions, Stimson instead issued a political statement which subsequently became known as “the Stimson Doctrine.” It simply said that the United States would not recognize any change in the status of a territory achieved by illegal means. Japan had seized Manchuria illegally. Therefore the United States would not recognize Japan’s occupation of Manchuria as legitimate.

Picking up the theme, the League of Nations adopted a resolution stating the same as a principle of international law.

The immediate practical effect of this high-minded talk was nil. But a seed had been planted.

When other fascist governments launched later invasions, other governments kept reacting with weakness which encouraged still more aggression. But they repeated the Stimson Doctrine.

On June 15, 1940 — shortly after France and all of Western Europe had fallen to the Nazis — the Soviet Union invaded Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. All three had been provinces of the Russian empire. All three had become independent after the First World War. And the Soviet Union turned all three into Soviet republics. The United States could do nothing. But on July 23, 1940, Sumner Welles, the acting Secretary of State, issued a statement in accordance with the Stimson Doctrine.

It became known as the Welles Declaration.

It reads:

During these past few days the devious processes whereunder the political independence and territorial integrity of the three small Baltic Republics – Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania – were to be deliberately annihilated by one of their more powerful neighbors, have been rapidly drawing to their conclusion.

From the day when the peoples of those Republics first gained their independent and democratic form of government the people of the United States have watched their admirable progress in self-government with deep and sympathetic interest.

The policy of this Government is universally known. The people of the United States are opposed to predatory activities no matter whether they are carried on by the use of force or by the threat of force. They are likewise opposed to any form of intervention on the part of one state, however powerful, in the domestic concerns of any other sovereign state, however weak.

These principles constitute the very foundations upon which the existing relationship between the twenty-one sovereign republics of the New World rests.

The United States will continue to stand by these principles, because of the conviction of the American people that unless the doctrine in which these principles are inherent once again governs the relations between nations, the rule of reason, of justice and of law – in other words, the basis of modern civilization itself – cannot be preserved.

The United States never accepted the Soviet occupation of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania.

In the American view, when the Soviets withdrew from the Baltic countries in 1991, those countries did not become independent. By law — “de jure” — they had always been independent. De facto control and de jure control simply aligned once again.

Following the Second World War, the Stimson Doctrine was enshrined in international law. Any country that attacks another commits a terrible crime, that law now states unequivocally, and if the aggressor attempts takes land from its victim, other countries must not deem the seizure legitimate and lawful. This is a basic principle of international law. As a United Nations resolution stated emphatically: “No territorial acquisition resulting from the threat or use of force shall be recognized as legal.”

That was a profound break from the world before the First World War. It made war unprofitable, or at least less profitable than if nations were allowed to take whatever they could sink their claws into. And it helped to maintain peace to a remarkable extent for 80 years.

But on April 23, 2025, Donald Trump threw all that away.

The US announced that Ukraine and Russia had to accept a peace deal on terms it outlined, or it would abandon the talks. And abandon Ukraine.

But Trump’s terms are not America’s. They are Russia’s.

The war would end where Russian and Ukrainian forces are now, with de facto control of all territory held by Russia remaining with Russia (which has already formally annexed some of that territory, a move not recognized internationally.) Trump’s terms would also require Ukraine to cede Crimea to Russia, effectively legitimizing Russia’s illegal seizure of Crimea in 2014. The United States would then formally recognize Russia’s sovereignty over Crimea. A decade ago, the United Nations, led by the United States, passed a resolution declaring Russia’s actions illegal in accordance with international law and American precedent going all the way back to Henry Stimson.

But Donald Trump is throwing all that away.

This is a betrayal of the most basic principle of the international order of the past 80 years. Given that the role of Judas in this drama is being played by the United States, the prime creator of that principle, and its prime guarantor, Trump’s action profoundly weaken the principle. And risk returning us to the international situation as it was before then — a situation which delivered two world wars.

But it’s also a specifically American betrayal.

It is a betrayal of the Welles Declaration and the steadfast refusal of the United States to endorse Russian imperialism.

And it is a betrayal of the Stimson Doctrine, whose wisdom was confirmed by the relative peace that has prevailed thanks to the elevation of that principle to international law.

It is a betrayal of great Americans. It is a betrayal of American values. It is a betrayal of American history.

And the world will pay the price.

About the paywall below

As I mentioned recently, I’m (slowly) changing this newsletter from hobby to job, meaning there will be more writing, and the writing will be more deeply researched. I’m also going to develop material for my next book (a social history of technology) right here.

That means I must now bow to the wisdom of Samuel Johnson’s famous observation — “No man but a blockhead ever wrote but for money” — and try to make some cash here. But I hate to shut people out. Can I accomplish objective one while avoiding undesirable outcome two?

I heard a Substack author who uses a “bonus material” model, meaning she writes a main piece or two then adds a series of short items after the paywall as a bonus for the sagacious and noble people who take out a paid subscription. I like that. And I think I’ll give it a try now.

As always, if you have suggestions on what I’m writing, or should be writing, or should be writing less, or anything else, I’d love to hear from you in the comments. Unfortunately, Substack doesn’t allow posts with paywalls to be open to anyone but pay subscribers. Which seems dumb. But you can leave a comment on the post preceding this one, which had no paywall. Or email me at futurebabble@gmail.com

And if you are able, please consider a paid subscription. It keeps the lights on.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to PastPresentFuture to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.