Today is “Canada Day” in Canada. Or as it is known in the Gardner household, where tradition and Parliamentary rules are held in higher regard than in the House of Commons, “Dominion Day.” (Canadians will get the joke. Or maybe a tiny handful of Canadians.)

But before I get to today’s post, I want to assure my non-Canadian readers that this newsletter is not going Canadian per se. It is written by a proud Canadian. And there has been a high volume of Canadian content over the last several months as our peaceful country is threatened by the Stay Puft Marshmallow Man rampaging across the landscape to our south. But this newsletter shall remain determinedly international in perspective (and will soon move toward the history of technology. Really. I’m getting there.)

I mention all this because I want to assure you that what follows is an aberration. Even for Canadians, this plunge into Canadiana and Canadian vexillogical history is, I am fully aware, purest dweebery. For foreigners, it is likely excruciating. If you don’t have a thing for flags and Canada, you should maybe skip it. But please don’t hit the unsubscribe button. I won’t keep doing this. Except… on July 4th. I have some riveting vexillogical content scheduled for America’s Independence Day.

But after that, no more.

Now on with the dweebery.

Every Canadian schoolchild is told that Canada’s national flag was adopted in 1965.

The few Canadian schoolchildren who remember that longer than 24 hours may also remember that this flag replaced another, which was most often known as the “Red Ensign.”

The reason for the change by the government of Prime Minister Lester Pearson was that Canada had fully come of age and some Canadians felt that the Red Ensign, with its prominent Union Jack in the canton — the top left quarter — made Canada look as if it were still a child of the Mother Country.

The switch was furiously debated, not least because the Red Ensign had been flown in the World Wars and Korea and veterans understandably hated the idea of retiring it. And it’s a damned good-looking flag. Objectively speaking. (Seriously, it’s gorgeous. If you disagree, I’ll slap you with a beaver tail.)

And yet, despite its rocky start, the new national flag was an undisputed success. That’s significant because, while successive governments from the 1960s on did away with old symbols and traditions and histories — bring back Dominion Day, dammit! — they had little or no success in creating new symbols, traditions, and histories. As a result, Canada is the rare country that has almost no widely used and recognized national symbols aside from the national flag and the stylized red maple leaf at its heart.

So why did the new flag soar when the story of national symbols is otherwise one of erasure, atrophy, and amnesia? I have a theory about that. And it is revealed simply by tracing the histories of Canadian flags.

Let’s begin by noticing the obvious: The modern Canadian flag is red and white with a prominent red maple leaf. And what is the Red Ensign? Mostly red and white with prominent red maple leaves.

As much as the new flag was a break with the past, it was an evolution, not a revolution.

Now let’s trace changes backwards. First stop, 1957.

That was the year that the Red Ensign seen above emerged from the previous Red Ensign, which is this:

Yes, they look identical. But notice the maple leaves are green. In 1957, they were made red, on the flag and the national coat of arms. The reason was aesthetic: Red maple leaves tied into the dominant red of the flag.

As I mentioned, veterans loved the Red Ensign.

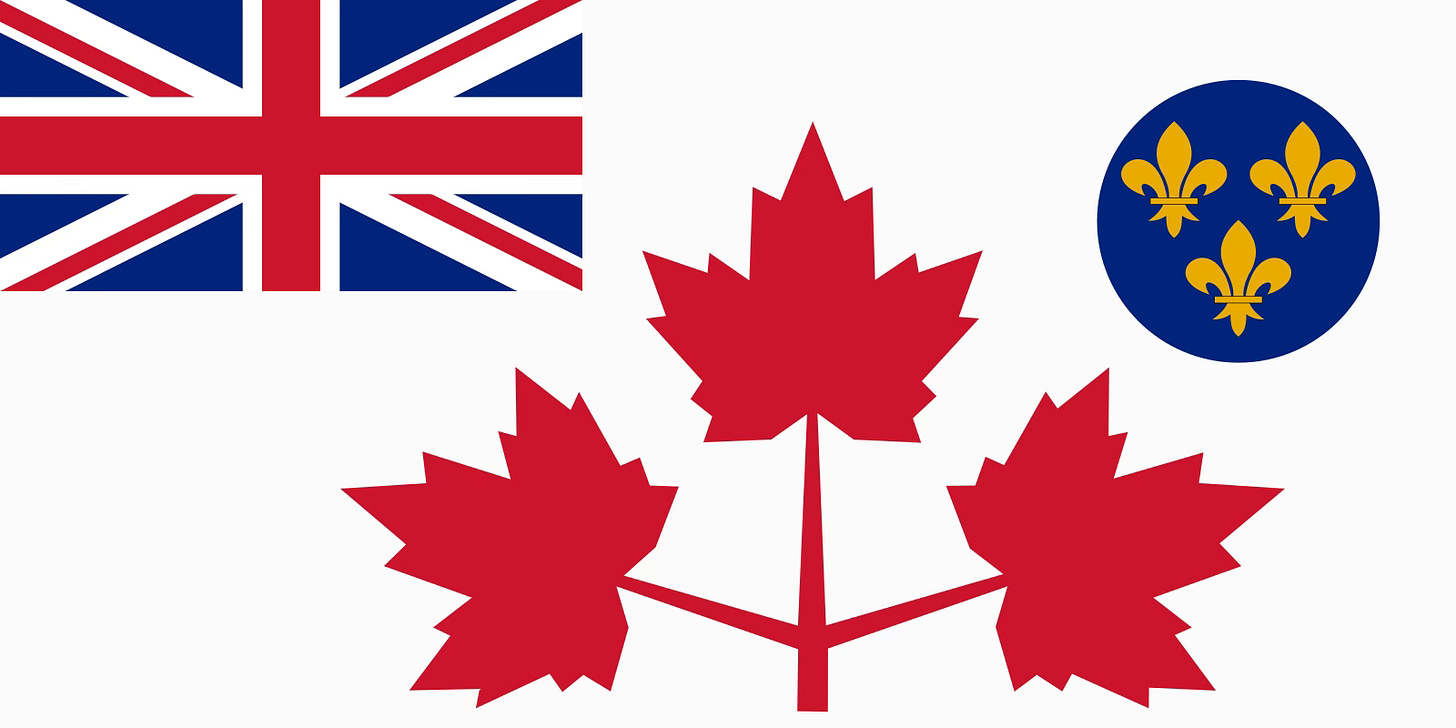

But during the Second World War, after the Canadian Army upgraded its official name from “militia” to “Army,” it briefly adopted the flag below. Some liked it. But it failed to catch on.

This design is typical of many proposals for new flags that rested on the idea that Canada was a creation of “two founding peoples,” the British and the French. That’s mostly myth. But it was popular myth for generations. (Notice also that the leaves are red. Canadians argued for decades about whether the leaves should be red or green. Backers of the latter said green leaves were symbols of life and vitality while red leaves are about to die and drop off the tree, which is not auspicious as a national symbol; backers of red said, well, green is fine on leaves but, well, it’s green.)

Moving backwards in time, the next significant vexillogical change came in 1921, when a new national coat of arms was created. That version is the one on the Red Ensign above, with green leaves.

It consists of ancient national symbols of England, Scotland, Ireland, and France. But note that the fleur-de-lys, which had been on the British/English monarch’s coat of arms for centuries as a symbol of the monarch’s claim to the French throne, had been removed more than a century earlier in Britain. So why was it here? Likely as a symbol of the French people and language in Canada. Combined with the other symbols, which are the component peoples of the British Isles (once again leaving out the poor Welsh), it is, as far as I can make out, a nod to the two founding peoples idea. And it became the dominant symbol on the Red Ensign.

The other important milestone was the adoption of red and white as Canada’s official colours. Why red and white were chosen was never made clear.

But red and white — particularly red — were widely known and used as Canadian symbols, most prominently in the Red Ensign. The ribbon colours for the first Canadian military medal issued — for the defence against Fenian raids from the United States — were red and white. And red and white became the colours of the flag of the Royal Military College in Kingston, which is unchanged to today, and looks strikingly similar to the modern flag for the simple reason that it was a key source of inspiration of the new flag’s design.

But now you’re dying to know: If the Red Ensign was changed in the 1920s by the addition of a new coat of arms, what was it before?

Below is a Canadian Red Ensign flown in the Western Front during the First World War. (It’s now in the collection of the Imperial War Museum, London.)

If you’re Canadian, you may recognize the four components of the coat of arms. They are the arms of the four provinces that originally founded Canada in 1867 — Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia.

But, if you are a dweeb like me, you may object: The First World War was 1914-1918. By then, several more provinces had joined Canada. Where are there arms?!

Great question! In fact, the flag above is out of date. By the time of the Great War, the arms, and the Red Ensign, had been changed with the addition of new coats of arms. Several new designs emerged.

Following is a closeup of a small flag I have that has all nine (sans Newfoundland) provincial arms and dates from around the First World War. (Yes, I collect flags. I have most of those I’m writing about here. And yes, I fully admit, acknowledge, and accept that this renders me a dweeb.)

The problem is that simply merging four, five, six — eventually nine — provincial coats of arms creates a national coat of arms that is a dog’s breakfast, to use the preferred vexillogical term.

Aesthetics weren’t the sole concern driving the changes in the 1920s, however. Canada’s enormous contribution to the First World War victory, then Canada’s involvement in the peace negotiations, led to a surge into patriotism that demanded stronger, standardized symbols. The maple leaf had been used as a symbol by French Quebecers for centuries but by the late 19th century it was a national symbol (The Maple Leaf Forever was written in 1867) and its use in the war — on uniforms and propaganda — made its prominence soar. These circumstances led to the changes in 1921 and the newer version of the Red Ensign. Which is, from an aesthetic standpoint, a much stronger flag.

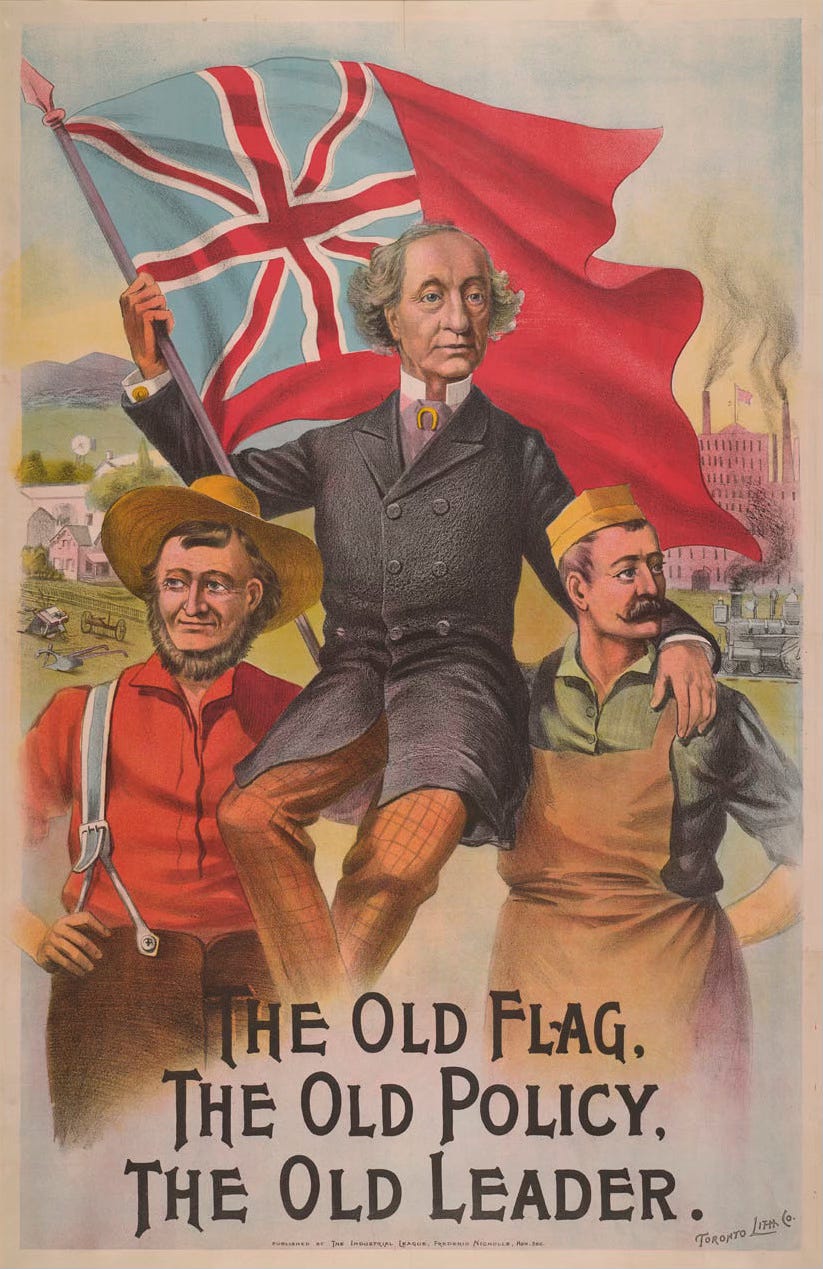

So, what, you may ask, was the national flag at the time of Confederation in 1867? There really wasn’t one. The Union Jack was routinely flown everywhere and it was as much a patriotic symbol as the red maple leaf is today. But in addition, there was an informal Red Ensign, with the red field left blank, that seems to have been used almost from the beginning. Sir John A. Macdonald used it in a famous campaign poster and permitted it to be flown over Parliament.

Macdonald tried to get official authorization for the flag as the flag of Canadian merchant ships, which had to be given by the British admiralty. It was refused. But the use of the Red Ensign as a distinctively Canadian flag on land grew organically, and in 1891, the British admiralty finally gave permission to fly the flag as the marker of Canadian ships.

Now, you may think I’ve taken this story back to very beginning. So this is the end. Or perhaps you wish this were the end. But it’s not — not by a long chalk, as the British say.

The fact that the British admiralty was involved in authorizing the Canadian Red Ensign isn’t a peripheral quirk of history. In fact, the Royal Navy is central to this story. And it’s a long, long story.

National flags as we know them are mostly an invention of the 18th and 19th century. Before then, the most prominent flags were those flown by ships which served the very practical purpose of identifying who controlled the ship. To be seen at a distance, they needed to be big. And bright.

As far back as the 16th century, English navy ships were organized into three (or four) squadrons which could be identified by the colour of the flag they flew — red, blue, or white. These squadrons came to be named after their colours. In the same century, the practice of sometimes putting the Cross of St. George in the canton of a flag was becoming widespread. Put a Cross of St. George in the canton of a red, blue, or what flag and you get what we would recognize as the Red Ensign, the Blue Ensign, and the White Ensign. As Britain explored and expanded, these flags were by the far the most prominent symbols of British power seen around the world. (I’m simplifying massively. British naval history is ridiculously complicated. Here’s a starter.)

In the mid-19th century, the Red Ensign became the exclusive flag of British merchant vessels while the White Ensign was the principal flag of the navy and the Blue Ensign became a lesser flag of the navy. (Again, simplifying. Naval history hurts my head.)

By the late 19th century — at the height of British imperialism, when the British ships dominated the seas the world over — it was common to adapt these flags to particular uses by placing a symbol or coat of arms in the fly. And that is when Macdonald and backers of the Red Ensign entered the story.

In other parts of the British Empire, similar stories unfolded, but rather than embrace and evolve the Red Ensign, they chose the Blue. Hence, the modern flags of Australia and New Zealand, to name only two of literally hundreds of examples.

Now, back to my original point about the success of the 1965 flag.

Why did it succeed? It didn’t invent anything new. It simply picked up existing elements and reworked them. All of those elements had deep cultural roots, some going back centuries.

In short, the flag succeeded because it was an evolution, not a revolution. Which is the Canadian way.

Now I’ll finish on a little note of patriotic optimism.

Yesterday, on the drive from my cottage the local grocery story, here in small-town Eastern Ontario, I was stunned to see an explosion of flags. Big flags on poles and porches and the sides of barns. Little flags carefully placed in straight lines along the edge of the highway. At house after house after house.

Canadians have never been big flag-wavers. The Canadian broadcaster Peter Gzowski once asked Canadians to complete the sentence “as Canadian as…” The winning entry: “As Canadian as possible under the circumstances.” Understatement is our thing and we’re immensely proud of our humility, so we generally leave the chest-beating and flag-waving to our excitable neighbours.

But today, if my drive to the grocery store counts as solid social science, there is a veritable explosion of flags in this fair Dominion.

I can guess why. You can, too.

So I’ll close with the best of the long-forgotten lyrics of The Maple Leaf Forever.

At Queenston Heights and Lundy's Lane,

Our brave fathers, side by side,

For freedom, homes and loved ones dear,

Firmly stood and nobly died;

And those dear rights which they maintained,

We swear to yield them never!

Our watchword evermore shall be

"The Maple Leaf forever!"

Allow me to translate that into language more familiar to the Stay Puft Marshmallow Man: We kicked your ass before and if you push us we’ll do it again.

God save the King! And happy Canada Day!

Dan,

It should also be noted that the Red Ensign was never the official National Flag of Canada de jure, but was only the National Flag of Canada de facto:

"The Canadian Red Ensign was the de facto Canadian national flag from 1868 until 1965. It was based on the ensign flown by British merchant ships since 1707. The three successive formal designs of the Canadian Red Ensign bore the Canadian coats of arms of 1868, 1921 and 1957. In 1891, it was described by the Governor General, Lord Stanley, as “the Flag which has come to be considered as the recognized Flag of the Dominion both afloat and ashore.” Though it was never formally adopted as Canada’s national flag, the Canadian Red Ensign represented Canada as a nation until it was replaced by the maple leaf design in 1965."

Ronald A. McCallum

Source: https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/red-ensign

P. S. I am of British/Anglo-Argentine/United Empire Loyalist background. My parents were from Argentina: my father was born there with a British (Scots) father and an Anglo-Argentine mother; and my paternal grandmother's paternal grandmother was born in New Brunswick of United Empire Loyalist stock from Rhode Island.

Great column. Thank you.