“The proposition we begin with is this: The most urgent problem of civilized mankind is to constitute effective means of governing itself where its civilization has already made its world practically one.” — Clarence K. Streit, 1939

I don’t think anybody aside from historians of the period remember who Clarence K. Streit was, but in the years leading up to the Second World War, he was a prominent American voice for an idealistic movement to ensure world peace.

Today, I want to give Clarence Streit’s long-forgotten plea a hearing. Because it is more relevant than ever. And that, my friends, is tragic.

As a young man, Streit volunteered to be a doughboy and he spent the First World War as an intelligence officer in France. He was an assistant with the American delegation at the Versailles peace conference, then a Rhodes scholar, and finally a foreign correspondent for The New York Times. He covered the doomed struggled of the League of Nations to prevent the return of war and in 1933 he devoted himself to a quioxotic but increasingly popular idea, work that culminated in his 1939 book, Union Now. It was a bestseller, in part because the legendary Henry Luce, publisher of Life and Time, was a fan. Luce even coined his famous term “the American century” in an essay which prominently cited Union Now.

In Union Now, Clarence Streit called on the world’s liberal democracies — specifically the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Ireland, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Norway, Denmark, Sweden, and Finland — to unite and become a single, federal nation.

There were many similar proposals between the world wars and in the years following 1945. This movement was sometimes called “Atlanticist” or “world federalist.” The goal was not to abolish countries and peoples, which is why the proposed unions were federations — so the existing countries would continue to exist, but beneath a larger umbrella.

The goal was to prevent war.

In the 18th and 19th centuries — as in every century that preceded them — international relations were governed by little that could be called law, not much more in the way of norms, and essentially no institutions. In practice if not in theory, it was a lawless anarchy. If it had a governing principle, it was “might makes right.” Or in the bleak words of the Athenians speaking to the Melians, whom they are about to slaughter and enslave, as recorded by Thucydides, “the strong do what they can while the weak suffer what they must.”

If the strong empires of Russia, Prussia, and Austria agreed to carve up Poland among themselves, and Poland lacked the strength to stop them, there was no one and nothing Poland could appeal to — so Poland was carved up like a Christmas goose. Complete extinctions of nations were rare, however. More commonly, great powers attacked lesser powers and extracted gold and land from their victims — as in 1864, when Austria and Prussia jointly attacked Denmark and helped themselves to the provinces of Schleswig and Holstein, which they jointly controlled. And now and then a great power would have a go at another great power, as Prussia did a few years later when it attacked Austria, defeated it, and took sole possession of Schleswig and Holstein. Or a few years after that, when Prussia routed France and helped itself to the French province of Alsace-Lorraine.

To avoid such losses and humiliations, the great powers sought alliances. So Germany agreed with Austria-Hungary that each would assist the other if Russia attacked. And France allied itself with Russia to defend against German attack.

None of this was new. In fact, it was quite ancient. History is stuffed with tales of great powers jockeying for offence and defence. But in other ways, the world of the late 19th century was unlike anything that had come before: Technology and trade were knitting countries and continents together with astonishing speed. Every part of the world felt so much closer to every other part; what happened in one place mattered so much more to every other part. The phrase “annihilation of distance” was one of the grand cliches of this era. A vast and diffuse world was rapidly becoming one.

The danger was obvious. In such an interconnected and interdependent world, any move by a great power could set off a chain reaction of events that could spark a war between all the great powers.

For many years, observers spoke with fear of the conflagration to come. But it didn’t. For decades. Many scoffed that it would never would, that the great powers would not be so stupid as to throw away the massive and growing benefits of what the world would later call “globalization.”

But in 1914 a car took a wrong turn, an assassin shot the Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the interlocked alliances kicked in, and the world erupted into the most terrible war in history — a war made all the more catastrophic by the very science, technology, and industry that had been rapidly improving life for so many peoples around the world.

After four years of slaughter, the collapse of empires, and the destruction of the world as it had been, the war ended and there was widespread agreement that an interconnected world could not go back to the anarchy of lawless powers. The nations of the world had to create laws and norms to govern relations and institutions where conflicts could be resolved. It was the only way to prevent another descent into hell.

U.S. President Woodrow Wilson was the leading exponent of this view but in the presidential election of 1920 the Wilsonian “internationalists” lost to the “isolationists.” Wilson’s League of Nations was created but without the United States as a member. America retreated behind its oceans, dramatically shrank its military, and let the rest of the world get on as it would.

Clarence Streit realized earlier than most that the League would fail and that without dramatic change an even more terrible war would come. He threw himself into the work of creating an international federation in 1933 and published Union Now in 1939 — six months before his long-feared war exploded in Europe.

In the book, Streit took statements of American leaders, past and present, and teased out their logic to show that the world must build international federalism to prevent a plunge into darkness. He quoted Franklin Roosevelt in 1936 comparing the international scene to a United States in which the 48 states of the nation are …

… “forty-eight nations with forty-eight forms of government, forty-eight customs barriers, forty-eight languages and forty-eight eternal and different verities, were spending their time and their substance in a frenzy of effort to make themselves strong enough to conquer their neighbors or strong enough to defend themselves against their neighbors.”

Then he cited Secretary of State Cordell Hull, saying the future would either be an anarchy of nations preying on each other, with wars sometimes vast and terrible, or law and reason would guide international relations. “As modern science and inventions bring nations ever closer together, the time approaches when, in the very nature of things, one or the other of these alternatives must prevail.”

The solution, Streit argued, is an international federation, which other nations could join as they brought themselves up to its democratic standards. Such talk at a time when Communists proposed a world dictatorship of the proletariat could be suspect, of course, so Streit emphasized that American idealists had long dreamed of such a future. Here is an 1875 statement of President Ulysses Grant’s that Streit highlighted:

Transport, education, and rapid development of both spiritual and material relationships by means of steam power and the telegraph, all this will make great changes. I am convinced that the Great Framer of the World will so develop it that it becomes one nation, so that armies and navies are no longer necessary.

When the catastrophe of the Second World War was mercifully ending, the old question rose again: How will we stop this madness from repeating?

Having rejected the internationalist view in 1920, having seen how isolationism failed to prevent hell’s return, having defeated fascism in a grand alliance, America’s leaders overwhelmingly approached the war’s end with an internationalist mindset.

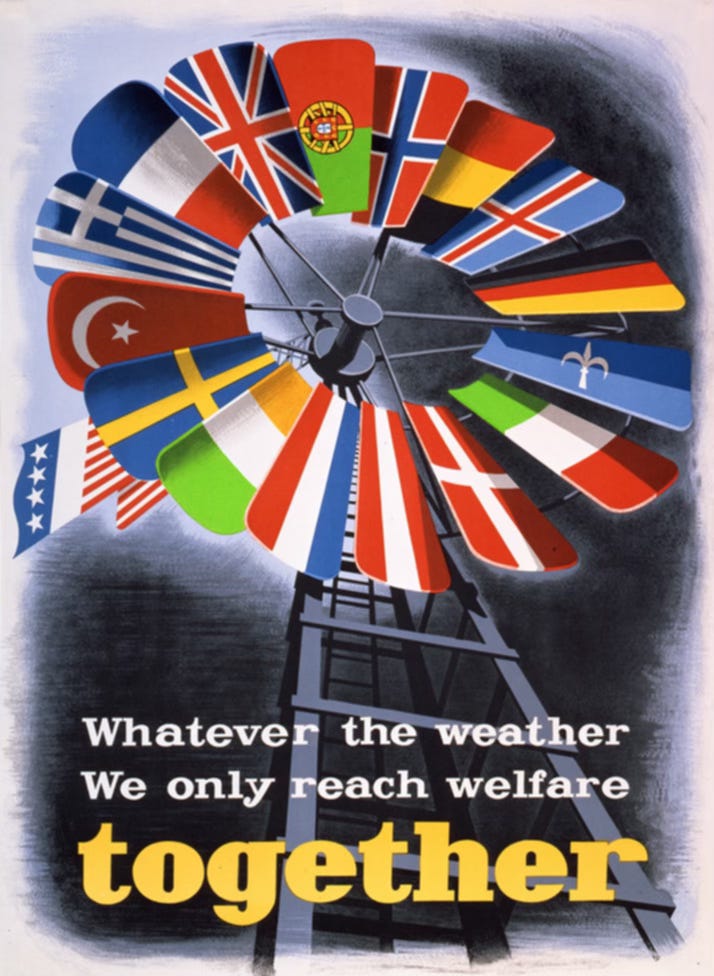

This is how an American-designed and American-led United Nations was created, along with the various agencies — like the World Health Organization — it entailed. This is how NATO came to be, with a list of members that is remarkably similar to Charles Streit’s list of potential members of a democratic federation.

America led the rebuilding of Europe. And America backed a huge new expansion of international law and norms. In particular, aggressive war was deemed an international crime — the Nazis were prosecuted on that charge at Nuremberg — which made it impossible to redraw borders by force. No more would the strong be free to snatch land from the weak. No more could tyrants order whole populations moved from one place to another, or to be liquidated altogether.

This was far short of Clarence Streit’s call for a federation of democracies. But still it was a giant leap toward a set of governing laws, norms, and institutions at the international level, all of it intended to prevent war. And while it was far from perfect, it was pretty damned good.

That is why it was such a shock when Russia attacked Ukraine and declared whole provinces to be its own. For most of human history, that sort of thing wasn’t remotely shocking. On the contrary, it was business as usual. The fact that people the world over were stunned actually demonstrated that the system created by the United States after the Second World War had successfully marginalized naked aggression.

Which brings me to Donald Trump.

When Trump said Greenland was important for American national security so Denmark would have to hand it over, and he wouldn’t rule out taking Greenland by military force, he did something much worse than threaten an old friend and ally. He violated the system of laws and norms America had created precisely to stop such bullying behaviour. Instead, he behave no differently than Prussia in 1864, when it attacked Denmark to strip it of lands Prussia coveted.

Many other actions of Trump’s confirm this was no aberration. He clearly sees a future in which great powers possess zones of control within which they can act with impunity. If a power wishes to invade and strip its weaker neighbours of territory, it can and it will. There is no law. There is no international community. There is only power. The strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must.

Donald Trump is tearing up the whole rules-based international system created after 1945, he is ignoring the catastrophic experience that inspired that system, and he is returning the world to the 19th century.

It’s impossible to overstate how foolish and dangerous that is.

Donald Trump is returning us to the era of great powers flexing muscles and taking land and jockeying for position with other great powers by forming alliances that create interlocking tensions. He is returning us to the era that exploded in August, 1914. Now, Trump is an incompetent man. Such a grand project would seem to be beyond him. But remember, this change does not require him to build, only destroy. And he’s shown he’s quite capable of that.

That said, if Trump has his way, there will still be a few differences between now and the world before the First World War. For one thing, the world is vastly more interconnected and interdependent today than it was. In 1914, it would take a week for an army to sail from New York to London but today even a 1970s-era intercontinental ballistic missile can fly from Moscow to New York in about 30 minutes, while new hypersonic missiles are a hell of a lot faster. And of course we have lots of nuclear warheads capable of incinerating cities in a blinding flash. In 1914, the world careened from assassination to catastrophe at what then felt like dizzying speed, but the tempo today is orders of magnitude faster. Judgements will have to be made in a snap. And the world could race from spark to conflagration — from Gavrilo Princip squeezing the trigger to Germans entering Belgium — in hours. Maybe minutes.

When annihilation takes only the turn of a key, there is no time to think.

Imagine a 19th century contest between great powers who feel themselves unconstrained by law or norms or institutions — who do not even fear becoming pariahs within the international community — except this contest is happening in the tightly interconnected, interdependent, digital-and-light-speed 21st century. How can that not end in a catastrophe that dwarfs the Second World War? Maybe sooner. Maybe later. But how can it not eventually produce a horror beyond imagining?

I don’t have an answer to that question. And that terrifies me.

As I watch the news in numb fear, a thought keeps coming back to me: The very last members of the generation that personally remembers the Second World War are almost gone. That era has ceased to be living memory. And in the same moment, we are on the verge of destroying the laws, norms, and institutions created in response to that awful experience.

Is that coincidence?

The outbreak of the Great War in 1914 was a long-feared hypothetical suddenly made vividly real. Four years of torment taught us that we must act to prevent such a thing from ever happening again. We tried. But that effort sputtered and failed. The result was another slide into horror. Then, at last, we acted.

Something like 100 million people died in the two world wars. But finally, we understood what people like Charles Streit struggled to make us understand. And we acted.

But all that living memory is gone now. All we have are old books. Like my copy of Union Now. It has a book plate from the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County, but it seems to have never been taken out or read by anyone. Printed in 1940, it looks brand new.

Maybe we can only learn from personal experience. And when all those who possess that experience die, the knowledge dies.

Maybe books cannot contain and transmit experience and memory. Maybe books are only ink on paper.

It feels like that today.

A very fine piece, Dan, and one that has elicited (apologies for tardiness!) my subscription. But the US it depicts was never the far-sighted, pluralistic megalodon of Atlanticist fantasies, nor of Trump's propaganda, the latter having twisted self-interested internationalism into an alt-history of being conned, duped, or squeezed by allies great and small, and in ways not coincident with US interests. If only! We fought the Kaiser for three years before doughboy saviors arrived to conquer the Argonne, and most Western historiography, and for two plus years a half generation later we stood the costly watch against Hitler, while American industry grew fat and a previous age's uber-rich argued that Europe was not Washington's business. Remember that Hitler declared war on the US after Pearl Harbor, and not the other way 'round. Likewise, it took effort and leadership - a key bit of both being Canadian - to get Truman and friends interested in what became a collective security pact. A stumbling one, to be sure, often nearly crippled by its own contradictions, but effective too, especially as the 'safe space' for the mitigation, even dilution, of national impulses. The continentalism surf has occasionally run high to our south (Senator Mansfield springs to mind), as has the perennial bleat that all US global commitments benefit Europe; hence, the eternal sourness of the US having fought in Indochina mostly alone, or, later, having had some presumably fickle friends who refused to let friends drive drunk in Gulf War II and stood down. (In each case, of course, the recalcitrant proved wise and the gunslingers idiotic.) The currents Trump rides have a long history, in other words, and those thinking it's all new, disruptive, and narrowly executive-led miss some small quotient of the point: he is as much symptom as cause, and the scarier thought, far more than his gang of grifters and fascists running amok in their ghoulish deceits, is that he actually commands the room and the room is comfortable with his treachery, guile, and baseness. 'Hitler's Willing Executioners' - as title or theme - is no doubt too strong. But is it demonstrably too weak? Thanks again for an awesome, thought-provoking read, as always.

The fly in your ointment is that there is very little of value left in the "international order," Dan. If there ever was any real value in it.

The U.N. is dominated by Jew-hating countries allied with Russia or China or both. It doesn't condemn Gaza, whose government has as its charter goal not merely the annexation but the annihilation of its neighbour. The leaders of Gaza make Putin look like a cuddly teddy bear by comparison - yet they garner more U.N. votes condemning Israel than every other hotspot on earth combined. UNRWA has been assisting the genocidal leaders of Gaza in every way for decades! (As we now know, so has USAID, which you heaped praise on just the other week.) The U.N. is on the wrong side of almost every issue, and mostly spreads corruption, Marxism and socialism, and sexual assaults around the world. And we won't know the half of it until the mandate of DOGE is expanded to the U.N.

It's the same with the I.C.C.: prosecuting war crimes against the leaders of Israel while doing nothing to condemn the aggressors of Gaza. Only the morally deranged still support the I.C.C.

China annexed Tibet after the U.N. was formed, and still has its eyes on Taiwan. Tibet is 5,556 times the size of Gaza (which is less than half the size of the City of Edmonton). The only reason anyone else in the world cares a whit about that zit of a death cult on the face of the planet is that Jews are trying to take out the trash.

The W.H.O. is an aspiring authoritarian outfit that covers up for Chinese malfeasance and negligence, under the guise of coordinating global heath efforts.

W.T.O. allowed China to become a member on the promise to reform its trade practices to conform with the norms of the international order. They haven't done so in 25 years, yet remain members in good standing. They abuse weaker trading partners with their Belt and Road Initiative, among many other traps.

Even NATO is dominated by nations that don't take their own national defense seriously - like Canada. It's a gang of softies who want to scold and tell the USA what they must and must not do with their blood and treasure. Europe has more than double the population of the USA, and five times the population if Russia. If they can't mount a credible deterrent to puny Putin all by their lonesome, that might go a long way to explaining why the world is in the state it is in right now.

Naïve optimism is no substitute for strategic geopolitical thinking. Unfortunately, ever since Lester Pearson, that's all the Canadian chattering class has.