At The Adjacent Possible, another Substack newsletter, Steven Johnson asks an important question: Why aren’t the world-altering triumphs of medicine and public health given greater prominence in textbooks, classes, and collective memory?

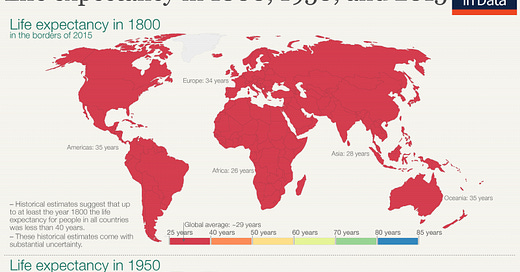

Johnson wrote an excellent book on the subject, Extra Life, and hosted a PBS series. I suppose you could say he’s biased. But there’s really no question he’s right. The life-saving progress of the last two hundred years is simply breathtaking. Take a look at the three maps below, from the indispensable Our World In Data.

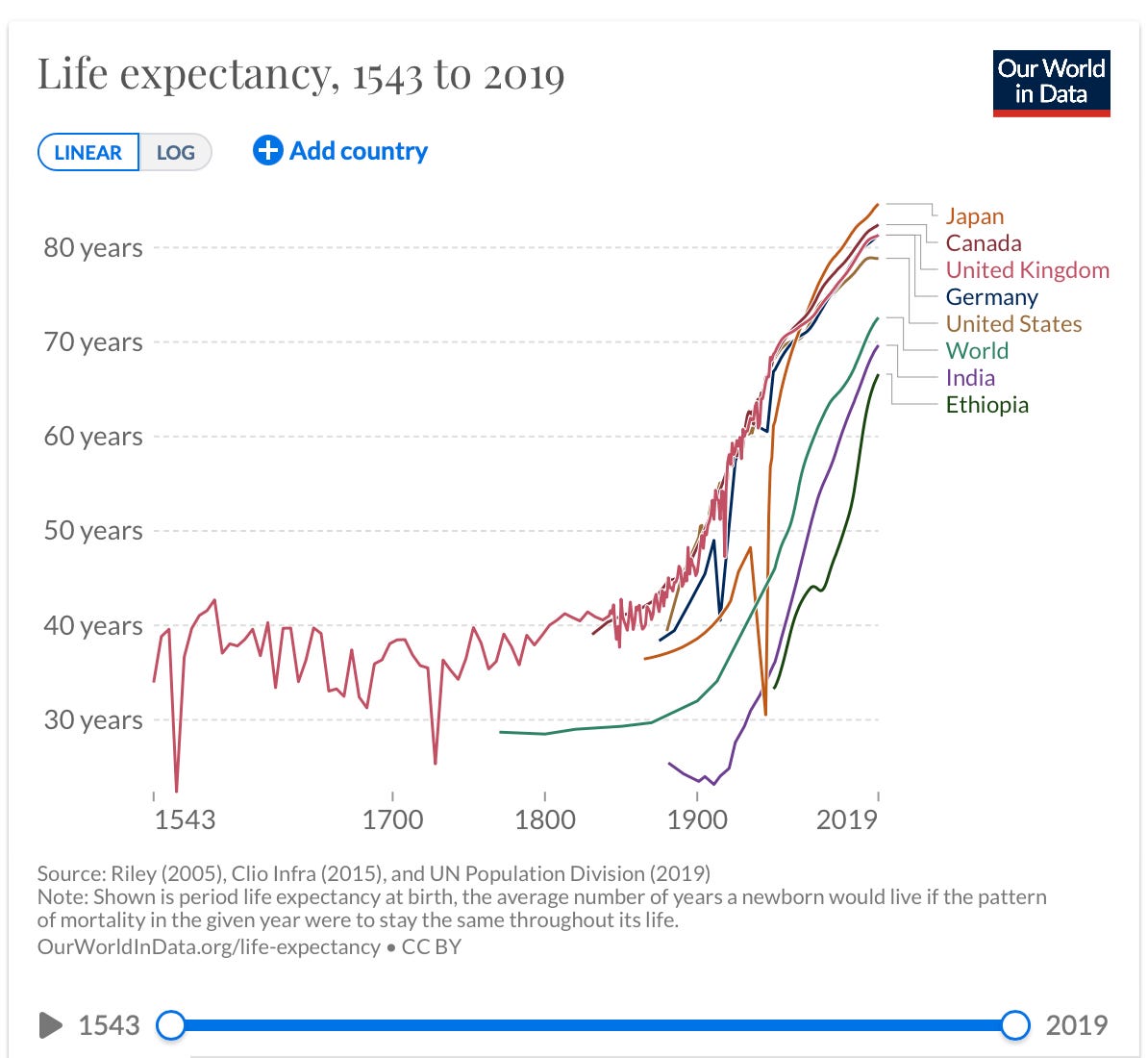

Now have a look the following life expectancy chart:

Note something else in that second chart that I alluded to in this piece: Compare the gains delivered by all that wonderful progress with the damage done by the world wars. I would never belittle the horror of the wars and the staggering toll they took. And yet, the gains humanity has made makes the losses of the wars look like little more than speed bumps.

But what do you see when you turn on the television? Yet another documentary about smallpox vaccination? A movie dramatizing the struggle to dig the London sewer system? A TV pundit talking about the lessons we can draw today from the history of food fortification?

No. You see yet another documentary about the Blitz, a movie about soldiers landing on D-Day, and pundits talking about the lessons of Munich.

Public memory reflects this disparity: Name two or three Second World War generals. Easy peasy, right? Now name the engineer who dug the London sewer system. (Give up? Click here.)

So let’s try to answer Johnson’s question.

Before I begin, I should note that what follows is only a partial answer. I don’t want to be reductionist. But I do think the following is a central part of the full answer:

We are not moved by What Didn’t Happen. We seldom even give it a moment’s thought.

There are various reasons for this. Which applies depends on the particular circumstances surrounding the thing that didn’t happen. They can be divided into three categories.

1/ We don’t know What Didn’t Happen

Imagine it’s 1998 and air safety experts are warning about a new and dangerous threat from terrorism.

In the past, terrorists hijacked planes and demanded to be flown to Cuba. Their goal wasn’t to maximize loss of life. Their goal was to maximize publicity. But some terrorist groups are growing more nihilistic. They still seek to maximize publicity but they do it by seeking to inflict as much carnage as possible. Terrorism experts are warning that if they turn hijack planes, they won’t demand to be flown to Cuba. They will deliberately crash them into symbolic landmarks or crowded buildings.

This warning doesn’t come entirely from conjecture. Four years earlier, a terrorist cell was caught before it could carry out its plane of hijacking a plane in France and crashing it into the Eiffel Tower.

Fortunately, the experts say, there is a simple, cost-effective way to dramatically lower this risk: Order all passenger jets to reinforce cockpit doors with steel and keep them closed and locked from wheels up to wheels down.

What I’ve describe here is real. Aviation experts really did issue this warning and make that recommendation.

But the Clinton administration refused because the airlines lobbied against it — reinforced cockpit doors weigh more therefore they consume more fuel therefore they add to the airlines’ expense. Immediately after the 9/11 attacks, the government ordered the change. It took the airlines one month to comply. The Bush administration publicly thanked them for their speedy response.

What if the Clinton administration had ordered the change in 1998? It’s highly likely 9/11 never would have happened. It’s also possible the chain of events 9/11 put in motion — including the invasion of Iraq — would not have happened, or would have happened differently.

If that were the case, would we now praise the Clinton administration for what didn’t happen? At the foot of the still-standing Twin Towers, would there be a statue honouring the aviation safety experts who advised the policy change? No.

Because it is extremely unlikely that we would know what would have happened if the administration had not made the policy change. In fact, no one but aviation regulators and the airlines would even know the policy had been changed.

We would have simply moved along with our lives in blissful ignorance.

2/ We only know What Didn’t Happen from statistics

Most of the progress Steven Johnson writes about doesn’t fit the category above. We generally have a decent sense of what would have happened if there were no vaccine against smallpox or if centralized water treatment had never been implemented.

We know this thanks to statistics.

We can look at trends before and after and calculate, with reasonable precision, what effect the measures had. The change tells us how many lives were saved. Or to put it the other way, how many lives were not lost — which is to say, what didn’t happen.

So there’s no reason to remain blissfully ignorant, one might think. And yet, collectively, we are. Why?

Because statistics are … statistics. Flat. Lifeless. Unemotional.

Most of all, unemotional.

We can understand statistics intellectually. And we can understand that those statistics are not mere abstractions. They represent people. Lives saved. Heartbreak averted. But can we feel that? No.

There’s a good reason for that. We didn’t evolve with statistics. Our ancient ancestors didn’t calculate lion prevalence stats to decide if they should worry about lions. They used stories. If you asked everyone sitting around the campfire about lions and everyone shrugged, you wouldn’t worry about lions. But if someone said they once saw another person taken down by lions and dragged away screaming? That story is vivid. You feel it. Your heart rate quickens. You encode the story in memory for future reference. And you worry about lions.

We can see the hollowness of statistics in what psychologists call “scope insensitivity.” If you say that for a donation of ten dollars people can help feed one hundred hungry children, you will get a certain response rate. Ask for the same donation to help feed one thousand hungry children, or one million, and the response won’t scale up proportionately. It may not scale up at all. Why not? Helping to feed hungry children is a good thing. We feel that. But that feeling doesn’t change whether it’s one hundred, one thousand, or one million children. Rationally, the statistics contain vitally important information that should significantly change the response. But to an emotional animal that gauges its responses by what it feels, they add little or nothing.

Good writers (even bad writers…) have always understood that stories trump statistics. That’s why the standard formula in journalism is to open with the story of an individual person with a story to tell, followed by the statistics that provide serious insight into the situation, and a conclusion that returns to the individual. To give statistics force — to make them capable of moving people — they must be converted to stories.

Steven Johnson is a master of this. Notice what he did in that article I linked to: He opened with Edvard Munch’s painting and discussed the death of Munch’s sister, Sophie, killed by tuberculosis at the age of fifteen. No statistic will ever hold a drop of the emotion contained in that story.

But notice also that the story Johnson tells is a tragedy, not the joyous tale of a life saved. That’s because, in storytelling terms, there is a fundamental asymmetry in statistics. Not only do we have a deeply engrained negativity bias that makes bad news more likely to grab our attention, and more likely to be remembered, converting statistics to emotionally gripping stories is far easier for bad news than good.

Homicide rates rising? Find a murder victim, tell the tragic story of that person’s death and the devastation inflicted on her family. Powerful stuff. Homicide rates falling? Find a person who wasn’t murdered, tell the story of his uneventful day at work and how his mother was mostly bored that evening while watching TV — then explain that we don’t actually know if this person would have been murdered if the homicide rate had not declined, but he and everyone else would have been at a somewhat higher risk, so maybe ….

Statistics are wonderful. They provide genuine insight. But they can’t tell us which kids would have died if not for the plunging rate of childhood mortality, only that lots would have. That’s no basis for a story that moves people because stories that move people are about individual, identifiable people. Not abstractions like “lots.” Or numbers.

One alternative is to use biographies of the people responsible for producing good news like vaccines and sewer systems. This is a staple of Steven Johnson’s work and nobody does it better. But no matter how skilled the writer, the story of the man who dug London’s sewers will never have the power of Edvard Munch’s sister slowly having the life strangled out of her young body by tuberculosis.

Progress is boring. Tragedy wins Pulitzers.

3/ We know What Didn’t Happen, but only vaguely

By January, 2020, Covid was known to be circulating in China. Epidemiologists knew it could spread beyond China’s borders and, if not contained, it could turn into a global pandemic.

This threat was well known. Epidemiologists had been warning about it for decades es. A few years earlier, Bill Gates had given a TED talk about the lack of preparedness for exactly this. So what if governments had listened, taken the threat seriously, ramped up preparedness, and put in place the best international detection and rapid response system money could buy? And, crucially, what if China hadn’t responded with secrecy and denial but instead worked with the international community?

It could have been stopped. Wrapped up by March, 2020. I’ll make no claim as to how probable that outcome was, but, yes, it could have come to pass.

What, then, could we have said about this Thing That Did Not Happen?

Unlike category one events, we would at least have had a sense of What Didn’t Happen. It could have gotten bad. But how likely was that? How many people would have died? What would the economic consequences have been? No one could say with any confidence. It could have been like the quickly forgotten H1N1 kerfuffle of 2009. Or the more serious SARS outbreak of 2003. Or the global catastrophe of the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918.

The Cold War offers some other examples in this category. In 1983, Soviet Lieutenant Colonel Stanislav Petrov decided on his own initiative to not alert his superiors when an American launch of five nuclear missiles was detected. It was a glitch in the Soviet computers, of course. What if Petrov had followed protocol and passed the alert along to the Kremlin? With only minutes to decide, how would the Soviet leadership have reacted? It could have been anything from an order to stand by and hold your breath — basically what Petrov did — to a full-scale thermonuclear launch. Then there’s the Cuban missile crisis. People often assume the only two possible outcomes to the crisis were peace and total thermonuclear war. That’s false. If serious hostilities had broken out, escalation to the-world-fries was not guaranteed. We don’t know what would have unfolded.

Of course, these possible outcomes aren’t total terra incognita. By carefully examining the evidence, we can judge which outcomes were more likely, which less. In fact, doing so would be no different than making a subjective forecast at the time of the event. But unlike forecasts, there would be no way to settle disagreements because we couldn’t simply let time pass and see what happens.

This is job security for historians, political scientists, and economists.

I’d like to offer a solution to this problem, as it leads to grossly distorted perceptions of history, as Johnson shows, and those misperceptions then inform decision-making in the present and plans for the future. But if there is a solution, I don’t know what it is. The best I can offer is the following reflection, which will sound familiar to regular readers.

People typically see the course history takes as singular. Because it is, in a sense. When Churchill became prime minister the first time — another Second World War reference! — he had a range of options, from continued war against Nazi Germany to capitulation. But once he and the Cabinet made that decision and acted on it, the other options closed. There may have been many paths forward, but Britain only took one.

The same is true for princes, prime ministers, and peasants. It’s one life, one day at a time, until we die. Look back and what you see is a path that may have twisted and turned but it was always and only one path.

So it’s understandable that we tend to think of the past, present, and future as a single track. And that what happened was what had to happen — rewind and rerun history a thousand times and the future would follow the same path every time.

But that is a highly consequential illusion. (More on this theme here.)

The array of possible futures is always huge. And that’s in the short-term. The further out you look, the wider the array. It rapidly becomes stupendous. Now, as a practical matter, much of that stupendous array consists of futures that are so fantastically improbable we can (usually) safely ignore them. But the basic concept holds: Always and everywhere, the future could take any one of an incomprehensible number of paths.

This isn’t easily held in mind. It’s not intuitive. It may even be a little unsettling. And when we look back, not only do we see history following one path, and one path only, hindsight bias urges us to think that the paths not taken — if we think of them at all — were much less likely than we perceived them to be when they were still open to us.

It takes concerted effort to see the future as the radically indeterminate thing it really is.

But it’s worth the effort. With this model of time, counterfactual thinking — thinking about What Didn’t Happen — is inevitable. That means thinking, “alright, this happened. But something else could have happened instead. Where would we be then? What does that tell us about the path we took. Or the path we should take in future?”

Like most things, if we engage in counterfactual thinking enough, it becomes habitual. Easy. Frequent.

And What Didn’t Happen has quite a story to tell. If only we would listen.

as a pathologist I can find a lot of observations that could have caused problems in a person’s or an animal’s life time yet did not. This makes me think of the danger of doing complete body scans as a kind of health check. You might observe something that will never manifest itself as a problem in the future. But you would not know.

I think our cognitive biases to fear and negativity, and to narrative/story, are most of the explanation. But the last part is the most interesting to me. We humans are such funny animals, both hyper aware of the indefiniteness of our experience of this life and the uncertainties of the future (because of that same fear bias?) and unable to really accept it. We invent methods and systems that help us cope with our predicament, help us make good/better choices despite the uncertainty - e.g., reading and writing, the scientific method, legal systems, democracy. But then we want to turn those choices into certainties. It seems to just be our nature and a cognitive process that is very hard to resist. Right now I am resisting the urge to say that we could finally overcome it once and for all if only we could devise a good method to help people avoid falling into it....