Why All Organizations Need History

Military leaders know the answer; few civilian executives do

I assume that you, like most my readers, are a fan of Swedish heavy metal. So my grabber opening today is a few lines from Steel Commanders by Sabaton, a band that mixes military history and power chords with the subtlety of a T-34 driving through a wall:

From the Mark 1's introduction to the beast known as the Leopard

With our Chieftains and Centurions, our frontline has been tempered

From the fields of Prokhorovka, to the shores of Overlord

The beginning of the victory, Shermans rolling on to Sword

Elizabeth Barrett Browning it’s not.

But this week I had the pleasure and privilege to take a ride on “the beast known as the Leopard,” one of the German-made Leopard 2 main battle tanks of the Canadian Army. The Leopard 2 has been in the headlines recently. It’s one of the tanks, along with the British Challenger and the American Abrams, that NATO nations, including Canada, are giving to Ukraine.

It is indeed a beast.

Weighing 70 to 80 tons, depending on the variant, trembling in the ground announces the arrival of the Leopard before the roar of its engine. But the beast doesn’t lumber. The Leopard’s top speed is a terrifying 70 kilometres per hour. It can spin in place, like a top. It can do doughnuts like a teenager in a Trans-Am.

“Hot damn,” said my inner teenager as we burned rubber.

If you’re still with me, and you’re not a tank fan, and you don’t love Swedish heavy metal, you may be wondering what this has got to do with my newsletter.

I am tempted to use this as an excuse to pick up from this piece and write about the evolution of the tank. But let’s go in an entirely different direction.

I had my little joyride at a Canadian Armed Forces facility that does maintenance for tanks and other heavy vehicles, although “maintenance” doesn’t do their work justice. When tanks are partway through their service lives, they are sent to this facility to be completely stripped down and pulled apart. Every scrap of equipment removed; turret, hull, and barrel separated. Worn parts are replaced. Larger components are sandblasted clean and repainted. Then the whole tank is reassembled.

Tanks go in looking like they’ve been through years of war — tank training is brutal — and come out looking like this year’s model in a showroom.

When I visited, there was one finished tank on site. A little detail painted on its side caught my eye.

Here’s a close-up photo.

Like ships and planes, tanks are commonly given names. Or at least nicknames. In the US, tank crews can choose the names. Some are bombastic. A few, hilarious. (My favourite: A tank commanded by a woman is called “Barbie Dreamhouse.”)

In Canada, the unit chooses names, so they’re a little less idiosyncratic.

The tank above has been dubbed the “Elizabeth II,” complete with crown, to honour the woman who was Canada’s head of state, and commander-in-chief, for 70 years. Given the lifespan of a tank, Elizabeth II will be making the ground shake for many years to come. I am an incorrigible monarchist with a deep fondness for my late sovereign, so that pleases me.

But I also find that choice of name fascinating for a very different reason.

If we set aside the uniforms and guns and whatnot, military organizations are not all that different from corporations, governments, and other civilian organizations. Which is not surprising. Military or civilian, organizations are simply collections of people trying to make decisions and get stuff done.

But there are important differences. One is history.

Militaries value the past. They see it as a resource. They draw on it to forge shared identity. They use it to inspire effort. History becomes a story about who we are, what we do, and why we do it. In this way, the past offers guidance for the present and future.

This is true of all militaries everywhere, as far as I know. But no one does it better than the United States Marine Corps.

The Corps turns young recruits into Marines with spit-and-polish drill. And history.

From the first day of boot camp, would-be Marines are told that Marines call each other “Devil Dogs” because, at the Battle of Belleau Wood, in June, 1918, the Corps fought with such ferocity that the Germans called them “Teufel Hunden,” or devil dogs. There is no evidence to support that story. But Marines all know it. And repeat it. And cherish it. The First World War has vanished from American popular memory, but if you’re a Marine, you know all about Belleau Wood. It’s sacred ground.

The Marine Corps is infused with history like that. The first two lines of the famous Marines’ Hymn — “from the halls of Montezuma to the shores of Tripoli” — mark an 1847 battle in the Mexican-American War and an 1805 battle in North Africa. In the Marine calendar, November 10 is celebrated as the Corps’ birthday because on November 10, 1775 — every Marine can tell you the Corps is older than the United States itself — the Second Continental Congress issued a decree creating a force of marines. (They don’t mention that they were modelled on the Royal Marines. Another missing fact: The principal purpose of raising the new force was to take Halifax from the Royal Navy. Still waiting, Devil Dogs.)

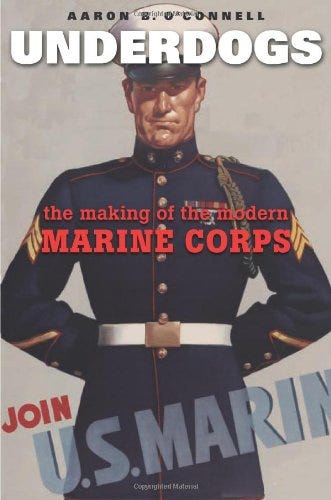

It’s not an accident that the Marines are so good at using history to craft identity. The Army is the army. The Navy is the navy. Why does the United States need the Marines? The Corps has wrestled with that question, and the threat of being scrapped, for more than a century. Developing a razor-sharp sense of who they are, how they are different, and why they matter was essential for their survival. (There’s a superb book about the Corps’ efforts to define itself and its mission.)

The Marines may make the most of history but all militaries do something similar.

Here’s one of a thousand possible illustrations:

Canada has a unit called the 427 Special Operations Aviation Squadron. It’s part of Canadian Special Operations Forces Command, or CANSOFCOM. (Another way militaries are different from civilian organizations? A mania for acronyms.) A motto of 427 Squadron is “low, fast and dark” because it flies the helicopters that drop operators precisely where they need to be and these operations are usually at night for tactical advantage. If terrorists were to, say, occupy a building and take hostages, 427 Squadron would pay a visit.

The squadron was formed in 1971. But if you ask people in the squadron when it was created, they won’t say 1971. They’ll say 1942.

Technically, that’s correct. Technically.

In 1942, the Royal Canadian Air Force created 427 Squadron to fly heavy bombers based in England on missions over Germany. The squadron’s insignia featured a lion so a British-based official with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer — then the most powerful Hollywood studio — got MGM to sponsor 427. MGM gave the squadron leader a gold lion statuette and squadron members were each given gold coins they could present for free admission at MGM’s theatre in London. The squadron, in turn, named its bombers after MGM stars. There was the Spencer Tracy. The Greer Garson. The Judy Garland. The Lucille Ball. (It’s generally forgotten today but Ball was a glamorous movie star long before she became a TV legend as a comedienne.) And there was the Walter Pidgeon, an honour presumably bestowed on the air crew that drew the short straw.

Below is a feature from The Lion’s Roar, the in-house magazine of MGM, published April, 1944. It’s all written in cheery language but the reality slips out in this one line: “The fact that the ‘ladies’ of the squadron have also been in there fighting is grimly attested to by the fact that the ‘Judy Garland’ as well as the ‘Spencer Tracy’ has been reported missing.”

When the war ended, 427 Squadron was disbanded.

Six years later, as the Cold War intensified, the RCAF needed a new unit of fighter jets. It didn’t create a new unit, however. It reformed 427 Squadron. Or rather, it “reformed” 427 Squadron. The new unit had different people, different planes, and a very different role. In fact, the new 427 Squadron had precious little to do with the old 427 Squadron, aside from the name.

But the name made all the difference. The history and regalia of the original 427 Squadron was now the history and regalia of the new 427 Squadron.

In 1970, that unit, too, was disbanded.

A year later, a new “Tactical Helicopter Squadron” was created. And again, despite the new unit being dramatically different, it was called the 427 Squadron. With all the history attached.

Today, the lion is still the squadron’s emblem and the unit still has MGM’s statuette — which is entrusted to junior officers who must care for it like it’s a general’s baby. Other mementoes from the squadron’s various incarnations are carefully preserved, displayed, and brought out on ceremonial occasions. “The objects are venerated pieces of history, but still instrumental,” an officer emailed me. “They’re not locked away to moulder, but handled and fought over, their talismanic power still in use.”

Members know this history and they see those young bomber crews from the Second World War as their ancestors. At an annual “Gathering of the Lions,” a formal dinner that gets rowdier as the night goes on, MGM’s lion is passed around with great fanfare. The night is capped with the burning of a piano, an air force tradition that seems to have started in Britain as long ago as the interwar period, although no one really knows when or why.

For militaries, history must be preserved and cherished. And if necessary, created.

That is profoundly wise. This sort of integrative storytelling is something that psychologically healthy individuals do automatically, compulsively. We need a story of ourselves, and no story is possible without a past. And all the same is true of human collectives. Stories integrate and inspire. They help turn collections of individuals into effective teams.

And stories must draw on the past.

This is why you name a tank after a deceased monarch who reigned for 70 years. That tank is now tied to all those decades of history. That tank has a story. And it belongs to the crew.

Outside militaries, there is much less appreciation that history is a practical tool, much less an indispensable one.

Sports are one of the few civilian fields that come close. Every team, in every sport, around the world, hangs banners for its victories and tells tales of legends. “This is who we are,” the stories say. “And this is what we will do. Each of us is part of something much bigger than ourselves.”

If you’re an executive in the civilian world today, that last bit is particularly important.

One of the major struggles organizations have today is hiring skilled and talented young people because theirs is a generation that wants and expects their jobs to deliver more than decent pay and occasional vacations. They want to believe that their work matters. They want meaning. They want to be part of something bigger than themselves.

To deliver that, corporations lean heavily on mission statements and conspicuous displays of social conscience.

What they seldom do is draw on the past.

If they need a new unit to do a new job, they create one. They attach no history. They tell no story. They simply assert that the new thing is important and now everyone should pull together as a team. Corporations even change names and brands, seeing a clean slate as an opportunity — without understanding that it can also induce a state of collective amnesia that corrodes any sense of belonging and purpose.

An individual with no memory of the past will struggle to form a healthy identity, and lacking that, will struggle at whatever he or she does. A team — or any collective — is no different. With no history, there can be no story. With no story, no identity. No meaning.

When I raise this with executives, I usually get one of two responses.

The first is, yes, I get why militaries do that. But we don’t have decades or centuries of history. We’re new. In fact, we work with evolving assemblages of partners. We have no history we can draw on.

I respond by advising them to read How Big Things Get Done. (I advise everyone to read How Big Things Get Done, but never mind.)

In chapter seven, Bent Flyvbjerg and I tell the story of the successful Terminal 5 project at London’s sprawling Heathrow Airport. T5 was a classic project of its kind, bringing together an enormous number of contractors and sub-contractors who had little in common beyond the fact that they were working on T5 together. The head of construction, Andrew Wolstenholme, had to turn these thousands of people from dozens of organizations into a single, effective team. He did, using methods we describe. One was a communications program structured around famous projects of the past — the Eiffel Tower in Paris, Grand Central Terminal in New York — and the tagline “we’re making history, too.” In effect, Wolstenholme told his people that the grand history of the past was their history, too — and they were writing the next chapter of that history. (Not coincidentally, I think, Wolstenholme is a former British Army officer.)

The wonderful thing about history is that there is heaps of it, everywhere. It just takes a little imagination to figure out how to use it.

The second objection I get from executives is that they don’t need history. They have a mission statement, after all. “Who are we? Why are we doing this work?” It’s right there in black and white. History is redundant. Inefficient. A waste of time.

Executives who talk like that don’t understand people.

Mission statements are abstractions. Human beings are not hardwired for abstractions. We are hardwired for stories.

You can tell young recruits that Marines are tough and brave. You can write that Marines are tough and brave into a mission statement and post that mission statement on every wall.

Or you can tell young recruits that a Marine named Daniel Daly shouted “come on, you sons of bitches! Do you want to live forever?” before charging the German lines at Belleau Wood.

One of those methods delivers words soon forgotten. The other lights fires that never go out. The Marines know which is which.

We all do, really. If you only remember one thing from this piece, what will it be? You know the answer. It’s what Daniel Daly shouted at Belleau Wood.

There’s a lesson in that memory for anyone who wants to turn a collection of individuals into an effective team.

Another great piece. This resonates with me on a number of levels, not least that over the decades I’ve associated with a number of Dragoons (as in Royal Canadian Dragoons, RCD, who “own” the Leopards), and in passing also my fair share of Leathernecks (US Marines) -- I’ll be forwarding this post to them. But more that your story of 427 Squadron mirrored my experience in the Navy where generally we recycle ships’ names precisely for the reasons you describe. “Perpetuation” is the term we use to carry on the fighting tradition of yesterday through the present and into the future. You’ve described it brilliantly.

As always, great insight. Placing whatever innovation you’re involved with inside the sweep of a story from history is vital for buy-in and success.