Will 2024 Deliver a 1924 Surprise?

Watershed years never look like it on the first day of the year.

Exactly one hundred years ago today, newspapers were full of the usual cheerful exhortations from local businessmen and other civic worthies. (“NEW YEAR GREETING to our FRIENDS and CLIENTS,” reads one in Sioux City, Iowa. “We advise you to start the New Year right and give us your application for a farm loan, early,” it helpfully suggests.) More serious efforts to take stock of the past year and look ahead to what was coming made for less pleasant reading.

“The New Year opens in an atmosphere of doubt and apprehension such as has not been experienced by anyone alive to-day,” declared a newspaper in Plymouth, England. Considering that almost everyone alive then had recently lived through the most devastating war in history, a global pandemic, the collapse of globalization and the destruction of the international order, that was quite a claim. But, yes, on the first day of January, 1924, people the world over worried that the grim news that had dominated previous nine years would get grimmer in 1924.

This is not how we think of the “Roaring Twenties,” of course.

In popular memory, the “Roaring Twenties” was a time of gin, jazz, and soaring stock markets. Everyone danced the Charleston. Electricity, telephones, and radios were suddenly everywhere and people raced around in Ford Model Ts. With airplanes in the skies, and skyscrapers transforming city skylines, the future was a technological paradise most people couldn’t wait to get to. The optimism was heady stuff.

But as with with most images of decades, this vision of the 1920s is, to a considerable extent, a mirage. For one thing, it describes the United States, and contrary to what many Americans (and quite a few others) seem to think, the United States is not the world. For Britain and many other countries, the 1920s never roared. And even in the United States, much of the decade was not spent dancing the Charleston.

In fact, America limped into the 1920s, wounded, scared, divided, and depressed. To millions of Americans, it felt like things were falling apart, at home and abroad. Only in 1924 did the economy and stock market really take off. Only then did the Roaring Twenties of legend begin.

That year was a true watershed.

We encounter years like it occasionally. Some mark the beginning of extended disaster. Others deliver a sudden reversal of decline and despair. On the minus side of the ledger, there is 1914, 1930, and 1968. Among happy watersheds, we can count 1948, 1983, and 1994. And 1924.

(Of course, labelling a year a watershed blurs and simplifies realities in much the same way, if not to the same degree, that labelling decades does. But we blur and simplify the moment we use language to describe reality, so it’s really just a choice of how much blur and simplification we’re willing to accept. Grant me this indulgence.)

As I’ve noted once or twice — or fifteen or sixteen times — people struggle to see the past as people experienced it at the time because we know how the movie ends. We know, for example, that in 1983 the recession did not worsen into a second Great Depression (something many observers feared at the time) and that awareness alters our perception of how likely that outcome seems to us now. A second Great Depression? In 1983? Ridiculous! That’s hindsight bias — a subtle but important psychological bias that causes us to consistently see the past as less uncertain than it was. And therefore less scary than it was.

This bias makes it hard to appreciate how genuinely surprising watershed years are. So let me explain what made 1924 a true watershed. And then, with minds suitably opened, let’s consider how 2024 could be another year to remember fondly.

But first, let’s imagine today is January 1, 1924.

Concerns vary from country to country, and most are of a more immediate nature. Will the government fall? Will stocks rise? The usual. But in the back of everyone’s mind is the state of the country and the world for the past decade or so. It’s been one lousy year after another. Will 1924 be more of the same? Or worse?

Not so long ago, people didn’t think like that. In the late 19th century through to 1914, technology and trade delivered rising prosperity in a process later generations would call globalization. And there was peace. Yes, people fretted about the threat of a general war among the great European powers but there hadn’t been such a war since Napoleon was beaten at Waterloo. And many smart people insisted that with the economies of the world so interwoven large-scale wars had become a hellish feature of a barbarous past.

Then came 1914 and the whole house of cards collapsed.

The Great War was far more devastating than anyone imagined when it broke out, but for the United States, it was, initially, a boom time. Until 1917, the United States remained neutral, but British purchasing agents fanned out across America to buy immense quantities of everything from American donkeys and horses to wheat and armoured cars. The worst problem the United States had was inflation, thanks to all that British gold.

But in 1917, the United States entered the war. By 1918, it had put four million men in uniform. Some 53,000 were killed in action, with most of the deaths inflicted in the final months of the war.

Though this period, and into the peace, the global Spanish influenza pandemic raged. Some 675,000 Americans died, a toll made worse by the fact that the victims were disproportionately young and healthy. (Soldiers in trenches and camps were perfect incubators.) History books often say the pandemic ended in 1919. It didn’t. Instead, Americans learned to live with the new plague as it returned in periodic waves that only gradually became less devastating through the 1920s. In time, the scourge came to be called — and belittled as — “seasonal flu.”

The war also promoted nationalism, nativism, and paranoia deeper and darker than anything seen before or since. Conspiracy theories — the Kaiser’s agents poisoned the toothpaste supply! — flourished. German-language newspapers were shut down and anyone caught speaking German in public — there was an enormous German-speaking population — was in danger of being lynched. Governments and courts supported it all. A filmmaker who made a movie depicting American soldiers fighting the British during the Revolution was actually imprisoned on the grounds that his movie was likely to hurt Allied solidarity.

Rage and fear continued in peacetime. Anti-immigrant sentiment ran so high that Congress passed a series of bills which all but shut down immigration. Anti-black racism exploded not only in the (now-infamous) Tulsa massacre but a whole series of similar pogroms — in big cities like Chicago and small towns like Rosewood, Florida — in which white Americans invaded black neighbourhoods, murdered on sight, and burned whole blocks to the ground.

Meanwhile, 60 to 80 people a year were lynched. Children and women crowded around corpses, eager to have their picture taken at what most people treated as nothing more than a thrilling community spectacle.

These years also saw the revival and explosive growth of the Ku Klux Klan. Mass rallies with tens of thousands of hooded marchers were a fixture of the era. Klan numbers aren’t certain but membership clearly approached or surpassed two million. In Indiana, one in five eligible residents were members. In Dayton, Ohio, an estimated ten percent of the population were Klansmen, and they repeatedly burned crosses on the campus of the University of Dayton, the former St. Mary’s University, which was Catholic. (The Klan believed the university’s ROTC program was cover for a Catholic army receiving training to fight Protestants. Paranoia is nothing new in American politics.) On the first night of the Christmas break, in December, 1923, forty carloads of Klansmen raided the campus, burned a cross, and detonated twelve bombs. Students and hundreds of neighbourhood residents counter-attacked and drove off the hooded terrorists.

Radicalism was not limited to the right. Anarchist bombings in 1919 prompted the first “Red Scare” and a a wave of official repression trampling civil liberties. Most of the public cheered. On September 16, 1920, anarchists detonated a massive bomb on Wall Street, killing forty people and injuring hundreds.

The unrest was enflamed by a dire economy. The end of the war had brought a massive slump in economic activity and an enormous surge in unemployment as doughboys returned from Europe. That seemed to abate in late 1919, but then came an even worse plunge. In 1920, the United States suffered the most severe deflation in its history. Stocks dropped into the basement. Another, milder recession started in 1923 and didn’t let up until 1924.

In 1920, when Warren G. Harding campaigned for the presidency by promising “a return to normalcy,” he was not only demonstrating that he was a bland man with no vision. He was appealing to a deep yearning millions of Americans felt. Even without looking abroad — as bad as America had it, Europe was in far worse condition — Americans had the sense that, as Yeats put it, “things fall apart; the centre cannot hold.” In this dangerous, scary time, rolling back the clock — making America great again, to borrow a phrase — was exactly what they wanted.

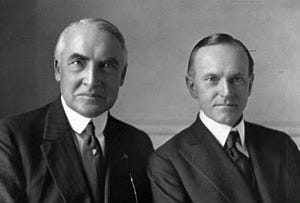

Harding won the presidency in 1920. But instead of “normalcy,” he delivered corruption — a weak, inept administration that allowed officials to stuff their pockets.

In 1923, the administration’s corruption started to come to light. At that moment, President Harding made his smartest political move and greatest contribution to the well-being of the United States by dying of a heart attack.

The Watershed

If you were an ordinary American on January 1, 1924, you wished ever a happy and prosperous new year. And you dreamed 1924 would grant you the same. But did you really think it would? Probably not.

But it did. In part drive by widespread adoption of new technologies, the economy surged and stocks soared. It was the beginning of an unprecedented bull market.

The popular mood shifted sharply. In November, Calvin Coolidge, Harding’s squeaky-clean successor, was returned to the White House in a landslide. (Coolidge won a whopping 54 percent of the popular vote even though a third-party candidate, Progressive Robert La Follette, took 17 percent.)

The booming economy helped let the steam out of the passions of those years. Terrorism faded. Anti-black race massacres all but stopped. Even the numbers of lynchings fell precipitously. And these changes were permanent. By 1939, when Billie Holiday sang the mournful Strange Fruit — a song written by a Jew, incidentally — the popular enthusiasm for lynching that made the murders possible had mostly evaporated and the annual number of victims was a small fraction of what it had been only twenty years earlier. The long era in which whole towns came out to join in the excitement, as if the circus had come to town, finally passed.

The explosive rise of the Klan was followed by something close to an implosion corruption, sex scandals, and inept leaders caused membership numbers to plummet. In only a few years, masks and secret societies looked ridiculous — and nothing is so dangerous to terrorism as mocking laughter.

Even Europe took a sudden turn for the better in 1924. Hyperinflations vanished. Stability returned across much of the continent and economics improved. Shaky democratic governments strengthened. In Germany, the nascent Nazi party, which garnered 6.5 percent of the vote in May 1924 elections (despite the party being formally banned and its leader imprisoned) lost more than half its vote in December 1924 elections. As Germany’s economy strengthened, the Nazis remained stuck in the political wilderness.

By the end of 1924, it felt like the fever that had gripped humanity for a decade had finally broken.

But on New Year’s Day, 1924, none of what was coming was clear. And if anyone had laid out this litany of good news exactly as it subsequently unfolded, they would have been sent to hospital because they had clearly consumed a bad batch of bathtub gin.

And 2024?

Today is exactly 100 years later. More than that coincidence makes me think 2024 could also be a surprisingly good year.

Let’s lay out the dream, shall we?

As always, it starts with the economy. And as always, the American economy in particular.

Surging growth. Rock-bottom unemployment. Solid rising incomes. Inflation placid. Stock markets shooting to new records. Wouldn’t that be sweet?

This year will also see an unusually high number of elections around the world, the most important — by a country mile — being the American presidential election in November.

Last year was a mixed bag. A wildly intolerant far-right party becoming the largest political party in the Netherlands, of all places. But in Poland, a solid centrist ousted the far-right party that had dominated for a decade. The dream is more of the latter, none of the former, and new wind in the sails of liberal democracy.

In the United States, the dream calls for some plain-vanilla Democrat, whether it’s Joe Biden or someone else, winning the White House in November. (I typically respect political differences but if you support a man who uses lies, threats, and violence to overturn elections, and increasingly uses nakedly fascist language, and envies dictators — or if you support a party that supports such a man — I cordially invite you to hit the unsubscribe button and go watch Fox.)

But the dream requires more than a Democratic victory. Donald Trump must be beaten so resoundingly that every Republican saner than Marjorie Taylor Greene is finally convinced that the madness gripping the party since 2015 is a political dead-end. The hardcore will never be shaken — Richard Nixon still had the approval of one in four Americans on the day he was forced to resign — but with their man and his manic energy gone they will not control the party. A turn toward moderation, or at least non-craziness, is possible. Republicans may even remember that, in contrast to serial loser Donald Trump, the most successful modern Republican won not with sneers, gloom, and hate, but smiles and optimism. If that happened, it would be morning in the GOP. And America.

And if the fever breaks in America, it would have a profound effect on the rest of the world. As I’ve noted many times, the world is obsessed with the United States, an obsession that goes far beyond the mere rational self-interest of monitoring the world’s most powerful country. American soft power is immense. I said earlier I’d love to see liberal democracy get some wind in its sails in 2024: It would be fair winds and following seas for liberal democracy if America got its democratic mojo back in 2024.

This very much extends to the war in Ukraine. Russia is a brutal dictatorship. Putin threatens to return the world to one in which invasions, land theft, and ethnic cleansing are legitimate tools of statecraft. Ukraine is an aspiring liberal democracy that wants to join the European Union. Russia must lose. And that means the slow abandonment of Ukraine we are started to see among right-wingers across the Western world must be stopped cold and replaced with a united front of unconditional support in the United States, the European Union, and all NATO countries.

Ukraine wins. Add that to the dream.

Of course, it would also be wonderful if some oligarch realized that if Putin stays in power he will spend the rest of his days shopping in Russian boutiques, and holidaying in Crimea — and take action accordingly. Of course it would be marvellous to see Putin in the prisoner’s dock at The Hague but that’s not a dream so much as fantasy. But an unexpected exit out a window? That’s feasible. A Russian tradition, even. Let’s hope “defenestration” is 2024’s word of the year.

So that’s my dream year. International law’s prohibition on nations invading and stealing land from neighbours is vindicated by the people of Ukraine and their allies. The rise of nativism and right-wing populism is checked in elections around the world. This is achieved in part by the American people, who deliver a thunderous repudiation — so unequivocal it even manages to knock some sense back into the GOP — of the greatest threat to American unity and rule of law since the Civil War. And that, in turn, is partly the result of a surprisingly strong economy delivering record-low unemployment, rising real wages, low inflation, and soaring stock markets — all of which remind Americans that even the average person is among the richest people who ever lived and it would be insane to jeopardize that by embracing a man who increasingly talks like it’s 1933 and he is speaking German.

What are the odds of that? I think it has a significant chance of coming to pass. Really.

Now, if you’ve read Superforecasting, I hope you just spat out your coffee. Because Superforecasting is full of lengthy arguments about how empty verbiage like “significant chance” feels information but isn’t really. In the paragraph above, I didn’t actually say anything. It feels like I did. But I didn't.

Given that this is New Year’s Day, and the media are stuffed with predictions, see how many you can spot that used that trick. If you read widely today, I expect you can easily get to double digits.

So let me turn my “significant chance” into something a little more substantive. I’ll spare you the lengthy details. They can get tedious and I’ve got real work to do. But here are the broad brushstrokes:

In my vision of 2024, the components are not separate and independent. So if one outcome happens, it makes another outcome more likely; if the first one fails, the second is likelier to fail. So let’s make the connections explicit and tackle them in order.

First up is the US economy. It has to be relatively strong, at a minimum. For a truly glorious 2024, it has to surprise to the upside, as 2023 did.

Most observers — the same people who once said a recession was inevitable, the only question being how severe it would be — now say the debate is between a “soft landing” and no landing at all. Translated, that means higher interest rates push inflation down, but at the cost of weak growth for a quarter or two, followed by improvement; or, as in the final quarter of 2023, growth is strong and rising, inflation stays down, and it’s away to the races. I’ve seen strong arguments for both propositions and I’m no economist. I’ll split the difference and say there’s a 50% chance the US economy will roar in 2024, but it looks pretty good in any event.

But as many observers have noted recently, economic reality and economic perception are very different creatures. And in elections, it is perception that matters.

As many observers have noted, the gap between popular perception of the state of the economy in 2023 diverged hugely from what the statistics say. The economy surged. Americans mostly remained gloomy.

There are a couple of reasons for that. Most important is politics. Americans are so political divided that, in poll after poll, for a large portion of the population, their perceptions of the state of America — on any dimension — depend on who’s in the White House. If it’s Our Guy, everything is the land of plenty. If it’s Their Guy, it’s an ash-covered hellscape. These rabidly partisan perceptions are not shared equally between the two parties: Republicans are much more inclined to this sort of blatantly biased analysis, with millions of Americans apparently convinced of Donald Trump’s claim that America was a hellscape until January, 2017, then it entered the greatest golden age in American history, which lasted until the hellscape returned in January, 2021. To say this version of reality is implausible is like saying it is unlikely the Toronto Maple Leafs will win the Superbowl this year.

The safest prediction I will make: This partisan skew isn’t going away in time for this year’s election. And it is what makes this election so very different from those in the past.

As we discuss in Superforecasting, the first step in any forecast should be the base rate. Here, that means asking “how often are incumbent presidents re-elected?” The answer: They are always re-elected unless the economy is in bad shape. Hence, even if the economy has a “soft landing” next year, Biden should win.

But those past results occurred in an America where even most self-identifies partisans could actually acknowledge economic reality, and vote accordingly. But that’s not the United States today. In 2024, the economy could grow 7%, inflation could be flat as the prairie, and everyone’s wages could rise by a quarter and I guarantee you that Donald Trump would describe America as ash-strewn hellscape and at least one-third of Americans would agree. In these conditions, a 1924-style Calvin Coolidge landslide is simply impossible, however strong the economy is.

So landslide is off the table. But my dream — not merely a Democratic win, but a clear, strong, undeniable win — could still come to pass with sufficient vigour to make Trumpian bluster about “rigged” and “stolen” sound like the ridiculous lies they are to everyone but total Trumpian tools.

That’s less likely with a soft landing, obviously, but still possible. Let’s put that at 25%. But if the economy goes to soar? I think then it’s very likely. Let’s put that at 60%.

Two reasons. One, abundant research shows the majority of Americans do not merely not support Donald Trump. They despise him. And they would walk over glass barefoot to keep him from returning to the White House. The polls which show Trump neck-and-neck with Biden, or even slightly leading, do not register those passions because the election is still a distant hypothetical. As November approaches, that will change.

The second reason is the perception of inflation. People hate it more than any economic condition save their own unemployment, so when it surged, anger and gloom were perfectly predictable. But as Robert Shiller has described extensively, people have little understanding of inflation. Most believe, for example, that if rising inflation means higher prices, the end of inflation means prices should drop back to what they were. It doesn’t. That would be deflation, which is even more destructive than inflation. What happens instead is that, in time, people get used to what they previously considered high prices and start to treat them as the new normal. If those prices subsequently do not rise rapidly, inflation fears slowly fade. So if inflation really has been beaten, it’s literally just a matter of time before the perception of inflation fades and people start to feel better about economic conditions. We’re well along in that process. If inflation is indeed down, and stays down, I predict that by November “inflation” is a word heard that will rapidly fade.

To sum up: In a soft-landing scenario, I put a narrow, 2020-style Biden win at 40%, a stronger, more convincing win at 25%, and a narrow Trump-win (not of the popular vote, only the Electoral College) at 35%. If the economy roars, 1924-style, I put a strong Biden win at 60%, a narrower Biden win at 30%, and a Trump win at 10% (thanks mostly to the Electoral College advantage and a friendly Supreme Court).

Predicting how the Republican party will react to these outcomes is harder, mostly because so much of the party base now lives in a parallel universe where basic facts disappear into black holes and rational calculation means something only a native of that universe can comprehend. But a narrow Biden victory? I find it hard to imagine how that doesn’t turn into more of the same. Eventually, senior Republican politicians and donors who privately hate and despise Trump — that’s most of them — will get tired of letting a delusional base drag them from defeat to defeat. But experience has taught me not to underestimate their cowardice. It will likely take another electoral cycle or two before they locate their spines. A strong, compelling win for Biden, however, might accelerate that process, particularly among the big money people. And even the craziest Republican politicians will sit up straight when the donors rap their knuckles. Probability? Total guess but I’ll say 60%.

If Biden wins so convincingly that even Republican leaders dare to suggest the Party of Lincoln should once again say democracy and rule of law are good things, and dictators are not, the ripple effects abroad will be major. Far-right populists will suffer. Ukraine will celebrate. The scenario in which the international order is vindicated, Ukraine moves closer to European Union membership, and — dare to dream — the global decline of liberal democracy over the past 15 stops, or even reverses, and 2024 is remember worldwide as a pivotal year, starts to become a real possibility.

There’s that vague verbiage again. Because a serious analysis of that last line would be a huge undertaking and I don’t have time.

Let me end with a couple of observations.

There are lots of different outcomes involved in my dream. That means there’s a heap of probabilities at work. And when that happens, the probability of a clean sweep — of all the outcomes coming to pass — is Probability One X Probability Two X Probability Three, etc. Which causes the likelihood of a complete win to plunge.

In reality, it’s seldom that simple because the probability of each outcome is not independent of all the other outcomes. So if we get a strong economy, the probability of a strong Biden win goes up. But still, in general, the more times you need to roll the dice and win to take the grand prize, the less likely you are to leave the casino with a giant smile on your face.

So is it likely 2024 will deliver a 1924-style surprise? No. It’s quite unlikely, in fact.

But that sort of cold analysis is not usually how people assess scenarios. Instead, we tend to read them like literature, and when we encounter colourful details and outcomes that intuitively feel correct we use those feelings to judge the overall scenario. Hence, scenarios that pile up details and conditions and outcomes are likely to be judged more plausible than scenarios with fewer elements. Exactly the reverse of reality. Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky noted this tendency way back in the 1970s and suggested it was a reason for the popularity of the colourful and highly detailed scenarios peddled by pundits and consultants. Caveat emptor.

OK. I’ve poured enough cold water on my own exercise. I’ll finish with something a little more optimistic.

In 2020, we were reminded that if we face a small percentage of disaster in one year, we almost certainly will not be hit with that disaster, but if we face that same small percentage year after year after year, it is literally only a matter of time before we get walloped. The highly improbable is inevitable.

But the same simple math applies to the upside, too.

Surprisingly wonderful years like 1924 are highly improbable. But they are also inevitable.

Maybe we’ll get lucky this year. Maybe next year. But sooner or later, it will happen.

Hang in there.

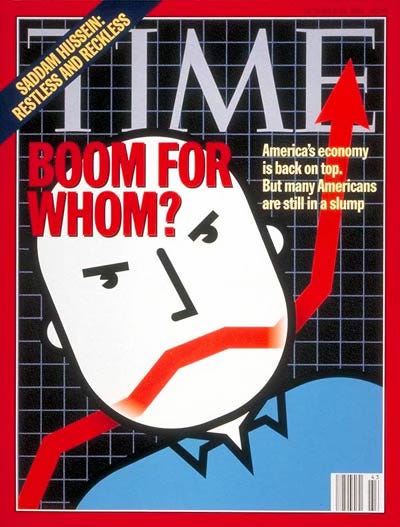

Postscript: On the subject of how thinking in decades obscures history, I always laugh when people say the 1990s were a golden decade. In 1992 a successful wartime president with a recent approval rating of 85% was humiliated in his re-election bid because the economy was so bad that Americans had fallen into a deep funk. Want to feel what the early 1990s felt like? Watch Falling Down, the 1993 Michael Douglas movie about an ordinary guy who loses his job and his mind and goes on violent rampage. Even in 1994 — a watershed year, when the American economy boomed and one of the biggest bull markets in history roared to life — Americans were grumpy as hell.

Here’s the cover of Time, October 24, 1994. Look familiar?

My observation about your ideologically captured behaviour requires expansion? Everything I’ve written is on display in what you wrote. It was an entertaining and interestingly analytical look at economics that was marred by your ideologically captured diatribe on behalf of your political preference. That’s when you left intellectual honesty for a captured belief system consistently displayed by much of the disconnected coastal media. When you write of sharp divisions you fail to recognize yourself as a core part of the problem. Biden as saviour? Trump as Hitler? Gee, that’s responsible opinion writing..... for one side of a propaganda war. Honest journalism would examine records in a comparative manner. Instead you steadfastly deny what you’re doing as you do it and keep demanding I appeal to other/higher authority when I opine on what you’re doing in an artful avoidance of self awareness.

The psychology that drives that consistently engages my curiosity. Thank you

That was a fun read. The century-spaced parallels have been fascinating me since 2019.

I’m always impressed by the blindness of both political extremes sitting in their silos, and you demonstrate yours well in a couple of places..... appearing mostly that of the disconnected-from-the-real-economy laptop class.